Michael Romanowski is a nine-time nominee and five-time Grammy-winning mastering engineer based in Berkeley, California. He is the owner and chief mastering engineer of Coast Mastering, one of the first certified immersive mixing/mastering facilities in the United States.

Romanowski is a pioneer of immersive audio, having built his first surround studio in 2001 and later added height channels in 2015. His first Dolby Atmos music mixes were completed in 2016, long before the format was adopted by the industry at large. Since then, he’s worked on iconic titles such as Mr. Big’s Lean Into It (1991), The Grateful Dead’s Workingman’s Dead (1970), and Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers’ Mojo (2010).

I recently had the chance to chat with Michael about his immersive audio journey, the complexities involved with mastering Atmos music, and where he thinks the industry is headed.

Perhaps it’s mere coincidence, but we’ve been able to issue quite a few Atmos titles you recently mastered–such as Peter Schilling’s 40 Years Of Major Tom compilation and Ryan Ulyate’s Act 3 (2023)–as hi-res digital downloads. So I wonder if you’ve been subtly pointing people my way?

I have! Glad to hear they’re coming to you, because I believe very firmly in what you’re doing with the TrueHD MKV files. I want people to hear the full-resolution versions of these mixes rather than lossy streaming.

I actually just did an online Atmos event with AES’ Philadelphia Chapter, where I interviewed Ryan Ulyate about the making of Act 3. We both made sure to mention that the album is also available as a download on IAA.

I really appreciate your support! I saw Sound & Vision Magazine published a great piece promoting Act 3 as well, so it seems like the word is getting out.

I’m surprised more people aren’t interested in the download route, because it doesn’t compete with streaming. Giving fans the opportunity to purchase the best-sounding version is only to the benefit of the labels. Your audience obviously already knows this, so I’m probably just preaching to the choir. [laughs]

I understand you were a very early adopter of Dolby Atmos, having set up your room way back in 2016 or 2017. Immersive music didn’t really take off until several years later, so what made you want to invest in the new format at the time?

Right away, I was amazed by the creative possibilities. I had built my first surround room back in 2001 at Coast Recorders in San Francisco, so I was already very familiar with 5.1–which to me was the first step in recreating the way we hear music in the real world.

When you go to a club or a symphony to hear live music, it’s bouncing off all the walls and coming from all around you. Ever since the early days of recorded sound on wax cylinders, we’ve been trying to recreate that experience artificially.

As the years went on, we came up with all these different miking techniques and formats–first stereo, then quadraphonic, 5.1, binaural, etc–in order to get closer to that real-life experience. To me, these new formats that utilize height channels are the ultimate realization of that idea. It’s been fascinating experimenting with it, seeing which kinds of music best lend themselves to this treatment and which don’t.

The science behind object-based audio is so interesting. It’s amazing to me how they’ve developed this “one-size-fits-all-format” format that will automatically adapt to any type of playback system, from headphones all the way up to a 7.1.4 or 9.1.6 speaker array.

Absolutely. We’ve gotten to a point where the devices are content-aware and the content is device-aware. It used to be that you’d put on an LP or a cassette through a stereo and had two channels, that was it.

Now, if you’re listening on compatible headphones, the device will sense that it’s being fed Atmos-content and then switch to binaural rendering on-the-fly. Or if you have a 5.1 soundbar system, the Atmos file will immediately know to render in six channels.

While I love the concept of a one-size-fits-all codec in theory–it simplifies a lot of the workflow on the professional side, like generating deliverables at the end of a project and then distributing them to DSPs for public consumption–its greatest strength might also be a weakness, because what sounds good on speakers doesn’t always translate to headphones.

You’re right. One of the biggest problems I see with the format right now is the idea of mixing with stems in order to match the stereo mix. The immersive version should stand on its own as a unique experience. If you’re starting with stems from the stereo mix sessions that are already processed and compressed in order to fit in a two-channel space, it’s just going to sound bad spread all around the room.

When you aggressively use compression and EQ in the stereo world, you’re pulling things out to the forefront. But with immersive–especially in binaural–you’re kind of pushing everything into the center of your head. It takes away the sense of space, which is what the format was designed for in the first place.

With some of the older catalog stuff, like The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper (1967), all those different elements were intentionally carved to fit into a mono picture. If you take those things and spread them around, it doesn’t really have the same impact.

I absolutely agree that using pre-processed stems to create an Atmos or 5.1 mix usually doesn’t produce great-sounding results. However, when it comes to remixing older catalog material into these multi-speaker formats, I do think it’s possible to craft an immersive mix that’s faithful to the original production while also creative in making full use of the extra space.

Yes. With a classic record, you have to honor the original intent because that’s what people know. There has to be a familiarity, but at the same time you can introduce that newfound sense of space. Whenever a new format is introduced, we always start with catalog work as a way to ease listeners into the new experience. Plus, the labels already own these assets and they want to monetize them.

I had the honor of working with Chuck Ainlay on Peter Frampton's Frampton Comes Alive (1976), the classic live record. Chuck’s one of the best engineers out there, and he really worked hard to make sure the immersive experience was faithful to the original. He went through all these two-inch tapes of different shows in the archive, trying to figure out which elements were flown in from what night. So for that project we had to start with a stereo mix, in order to make sure all the original elements were there.

There’s a spot in one song where you can hear a firecracker go off in the background. While this was technically a mistake, it’s now ingrained into people’s memories from decades of listening to the original LP. So we could have taken it out, but we left it in.

I’m a huge fan of Steven Wilson’s work for exactly this reason. He’s very good at creating immersive mixes that are simultaneously very familiar, but also revealing and exciting to listen to again even if the original stereo version is burned into your brain.

Oh yeah, he’s great. I’ve got lots of box sets and discs of titles he worked on.

There are definitely challenges with getting catalog stuff to work in immersive. For instance, I just mastered the new Atmos mix of Al Green’s Greatest Hits (1975)–some of it was recorded on 16-track, but other songs were 4-track. It’s just all over the place.

I also mastered Eric Schilling’s Atmos mix of The Bee Gees’ Timeless compilation (2017). He did such a fantastic job on that, I think it’s 21 or 22 songs in Atmos?

If I can say one thing about the Grammys this past year, being nominated for four out of the five nominees in the immersive category tells me that mastering is important. For every one of those projects, I worked with the original engineer to rebuild the original tracks from scratch. There were no stems involved.

Another one you worked on that I thought came out great was Peter Schilling’s 40 Years Of Major Tom - New Adventures. I’m really glad we were able to release that title as a hi-res download.

Yeah, I worked on that with Tom Ammerman. I don’t know if you heard the Kraftwerk stuff he did in Atmos, but that was how he came on my radar. I think it was a live box set? I reached out to him after hearing that and we ended up getting to know each other really well.

Since there’s no “master bus” in the session, how does one go about mastering an Atmos mix? In as much detail as you’d like, take me through your process and workflow.

While that’s technically true, there are some ways around it. Like you were saying, I was a very early adopter of Atmos and–at the risk of sounding maybe not so humble–I think I really did pioneer the idea of mastering the immersive world. This room was nominated for a TEC award in studio design, as the first purposely-built mastering room for immersive audio.

In a sense, the process for mastering immersive isn’t radically different from stereo. I always say that mastering is a state of mind. It’s really two opinions–the artist’s and the engineer’s–then a process of deciding what the final product should sound like.

The first thing I do is sit back and just listen. I’m not doing anything with plugins or gear yet. Once I know what it currently sounds like, I can start to think about what it could sound like. So really, mastering is just a process of getting from that point A to point B.

I actually think mastering immersive is more important than stereo, because there are so many places where things can go wrong. As you probably know, there are so many different types of deliverables. You need to pay attention to these things, because sometimes different labels require different types of files.

Plus, we don't have the ability to do the ‘car test’ like in the old days. You can’t just run off a cassette or burn a CD to play in the car. So being able to check how the mix sounds in another room helps give artists as well as the engineers confidence in their mixes.

One of the most important aspects of the process for me is dialogue with the mix engineer, because–given the nature of the ADM files–I can open up the mix on my system and access all the individual beds and objects. If there’s a violin in one of the side speakers that sounds kind of bright and upfront on my system, I could easily go in and adjust that element. But maybe the artist or engineer intended for it to come off that way? So I’ll be sure to touch base with them before I make any adjustments like that.

Overall, the #1 rule of mastering is to do no harm. You’re just trying to make the end product better, which sometimes means not doing anything at all. But there are important technical considerations, like making sure the final deliverables are in spec in terms of levels and length.

It’s fascinating how with Atmos, the ADM master essentially functions as both the final bounce/deliverable but also the session format. So you can open an ADM in any WAV editor and get access to the individual elements, but it’s impossible to play it back correctly without the Dolby Renderer to interpret the spatial positioning metadata.

I’m working with Jeff Balding, George Massenburg, and other members of the Recording Academy P&E Wing to put together some best practices and delivery recommendations when it comes to ADM files. An ADM for Sony 360/MPEG-H isn’t the same as an ADM for Dolby Atmos, so there needs to be some compatibility there.

To your point, anybody can take an ADM file into a DAW and start remixing it. It’s not quite the same as the session file–you don’t get access to the plugins and busing–but it’s probably as close as you can get.

Yeah, I can understand why the labels wouldn’t want those out in the public domain. That’s part of what I like about the TrueHD format–they sound essentially identical to the ADMs, but the individual elements aren’t exposed like that. It’s really a 7.1 file that has the ability to expand to a larger speaker array when played through compatible equipment.

That’s exactly right. You’re giving the listener lossless playback without any copyright issues for the labels. It’s a great way to release these mixes, and I hope IAA goes on to be synonymous with this format in the same way that HDTracks popularized hi-res stereo downloads.

With Atmos, it seems like every mixer has their own unique approach. Some work exclusively with objects, while others only use the bed–and every variation in between. Do you mix primarily with objects, or a combination of beds and objects?

It varies per project. Similar to you, I’m being sent files that have all these different variations in approach. For example, Chuck Ainlay uses multiple beds–one for reverbs, one for delays, another for background vocals, and so on. That’s kind of the same workflow used in the cinema world, having different beds for dialogue, effects, and music tracks.

There’s also the concept of an “object bed,” where you place static objects at the speaker positions and then pan through those. Some people claim that method gives a more accurate rendering. Ryan Ulyate’s Act 3 was done that way.

I’ve seen it all, and what I’ve learned so far–after all this experimentation and listening–is that it depends on the intent. The style of music should dictate the path forward of whether to rely on objects or beds.

Since the very early days of 5.1, proper usage of the center speaker and LFE continues to be debated. How do you feel about the center and LFE channels?

I think the LFE should be used for exactly what it was named for: low frequency effects. It’s meant for cannon fire and earthquakes, not to carry all the low-end in a music mix. I wouldn’t rely on it that way, because it’s one of the hardest variables to control in a consumer setup.

How do you know if they’ve calibrated it correctly? Chances are it’s dialed in for cinema reproduction, so it’s going to be running 10 dB hotter than on a music-based setup. I use it a little bit, but all the other speakers in my setup are full-range. Even the sides and wides go down to 35 hz. So there’s really no benefit to making heavy use of the LFE, at least in my view.

With the center channel, we’ve gotten so used to what vocals sound like as a ‘phantom’ center that it’s sometimes jarring to hear the voice actually coming out of a physical center speaker. There are some artists I've worked with that don't want their vocals isolated in the center, which as you probably know is a controversial thing going back even to the early 5.1 days.

You don't want somebody to be able to rip the vocal channel out completely and do something else with it. With the growing world of AI, being able to take individual sounds and repurpose them is going to be an issue moving forward that the industry will have to deal with.

The other issue is that a lot of people used to say the center channel was the “TV speaker” that’s unmatched and usually smaller than the rest of the setup. So you wouldn’t want to rely too much on that for full-range sounds like the kick drum or bass guitar.

I’m finishing mixing two Kenny Wayne Shepherd records in Atmos right now, and for this project I’m doing a combination of real and phantom center. The vocal is audible across the fronts, but a bit stronger in the center.

I can understand both sides of the debate. On the one hand, I like the idea of a dedicated vocal-only channel that the end-user can adjust to taste. That said, having the vocal isolated dry in the center channel can sometimes give the mix a sort of disjointed quality–like the singer is trapped in a box, separate from the rest of the band. There are so many interesting ways to present the vocal in Atmos–I’ve heard mixes where it’s suspended between the center and front height channels, which gives the impression of the singer standing right in front of you.

This goes back to what I was saying earlier about the creative possibilities of this format. Once we’ve moved beyond catalog mixes where you need to be reverent to the original stereo version, use of the LFE and center speakers can be dictated by content.

For example, on that Kenny Wayne Shepherd record there’s a distorted bass sound. In Atmos, I have the clean DI signal in the center speaker and the distortion mostly coming from the back. It all blends together on headphones, but the effect on speakers is really interesting.

Going back to what you were saying earlier about presenting the immersive mix as a totally unique experience rather than an expansion of the stereo version, one recent project I felt really followed that approach effectively was Peter Gabriel’s new album i/o. Hans-Martin Buff, the engineer who worked on the Atmos mix, told me that they overdubbed new parts just to enhance the spatial experience.

That’s awesome. I haven’t heard that Atmos mix yet, but people have told me great things about it.

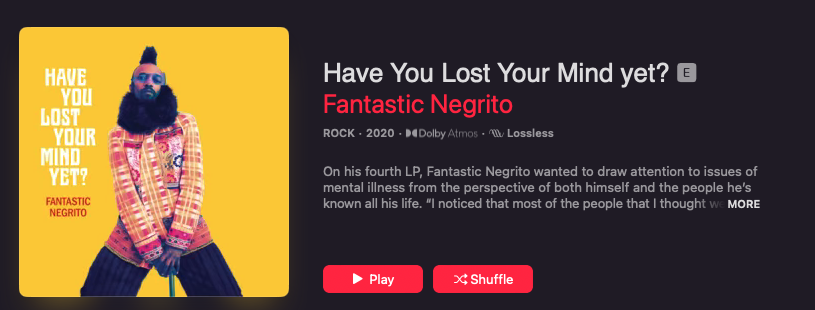

I had a similar experience remixing Fantastic Negrito’s Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? (2020) in Atmos several years ago. He came in to listen and I played him several other mixes to show what the format is about. He asked “what are my options?” and I remember saying “well, we can adhere to the original or we can make it something different.” He said “I already have the stereo. Why would I want it to sound like that with all these speakers around me?” To me, that’s a perfect example of the creative spirit. It’s okay to go in a different direction.

With the introduction of Apple’s “Spatial Audio” format, it seems most listeners are experiencing a binaural approximation of Atmos over headphones rather than the full immersive experience on a home theater setup. Is it difficult to simultaneously achieve effective results on both speakers and headphones?

It definitely adds another complication, because you’re trying to hit a moving target. Apple is constantly making updates and changes to the Spatial Audio algorithm, so you can’t always predict how your mix will translate. I’m not a huge fan of the head tracking feature, at least for music.

I understand you’re set up not only to monitor in Dolby Atmos, but also Sony 360 Reality Audio. It seems like there’s a lot of content being created for this format, but very little investment happening on the consumer hardware side. As far as I’m aware, the MPEG-H format isn’t yet supported on most consumer AVRs–so it seems unlikely that they’ll ever catch up with Dolby, who’ve done a great job packaging Atmos into so many consumer devices.

“Catching up” is a good way to put it. There are now AVRs from Marantz, Onkyo, and McIntosh that support MPEG-H and 360RA.

I think there are definitely benefits to 360RA for headphone playback. You’ve got nine speakers in front of you: three on top, three at ear-level, and three below. In the gaming world especially–where you’re often looking up-and-down from a first-person perspective–it’s a better representation of how we actually see and hear.

I’ve noticed that a lot of albums under the Sony umbrella are in Atmos on Apple Music and 360RA on Tidal. For these projects, do you have to deliver unique masters or is it simply a case of converting an ADM to MPEG-H or vice versa?

There are examples of both. For me as a mastering engineer, having to deliver both Atmos and 360 is not unlike delivering a CD master and an LP master. They come from the same raw ingredients, but you do have to make changes.

At first, there was tedious work involved with converting an Atmos file to a Sony 360 file because the speaker configurations are different. There’s no LFE in 360, plus you have the extra set of speakers below ear-level. I have a prototype of a program from Sony that will convert from Atmos to 360 while keeping all the object metadata and binaural render modes.

Can you tease any upcoming immersive projects you’re involved with?

There are a few I can’t talk about, but I did just finish another George Strait record with Chuck Ainlay.

I love the Atmos mix he did of Lyle Lovett’s 12th Of June (2022), which you also mastered.

Yeah, that came out great. With both those projects, you’re dealing with an old-school crooner-type songwriter. It’s not meant to be a rollercoaster in immersive, like The Flaming Lips.

I'm also working with an Indian tribe in Michigan, that has never had non-tribes folk be part of powwow celebrations. They did a big powwow and we miked it up immersively. The dance has a lot of circular movement, so it really lends itself to spatial reproduction. It’s a fascinating project that’s historical as much as it is experiential.

As we talked about before, I just finished volume one of Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s new record in Atmos and I'm starting on volume two. Each volume has eight songs. He’s so good and his band is just fantastic.

I’ve heard people say that certain genres don’t translate well to immersive, but I don’t think that’s true at all. Some of the most impressive Atmos mixes I’ve heard are of relatively-sparse recordings done on 16-track or 8-track tape, like Van Morrison’s Moondance (1970). It’s just a handful of players performing live in the studio with very few overdubs, but it sounds massive.

Limitations often breed creativity. I mean, look at what The Beatles were able to achieve with a simple four-track recorder. If you’ve only got 8 tracks to work with, how do you make the music feel like it’s coming from all around you?

Many years ago, Eric Schilling and I did an Atmos mix of America’s “A Horse With No Name.” It was recorded on 16-track, and you could hear them slowly developing the song with each take. The ninth take was when when the magic finally hit, and then they added a few overdubs. Even with the overdubs, there were only 14 tracks of recorded information to work with. A lot of the harmony vocals were done with all three guys on one mic. So you don’t necessarily need 100 tracks of information to make an interesting spatial experience.

I imagine there would be similar challenges with remixing some of those classic Crosby, Stills & Nash records in Atmos. It would be amazing to hear the vocal parts in a song like “Carry On” spread out all around the listener, but I suspect all three guys were singing into one mic.

Yeah, the one mic stuff is hard to separate. There are tools to get around it, but it depends on how dense the mix is. I thought they did a great job with this on “Because” from The Beatles’ Love (2006). It’s three guys singing into one mic, but it translates to 5.1 really nicely.

It’s easy to be cynical about the future of immersive music, especially after so many failed attempts to bring it to the marketplace–quadraphonic LPs and tapes in the 1970s, 5.1 SACD and DVD-Audio in the 2000s, Pure Audio Blu-Ray in the 2010s, etc–but something feels different this time. It really is amazing to see how the industry at large has rallied around Dolby Atmos over these last few years, especially after the relatively-slow trickle of 5.1 music releases throughout the 2010s.

The key is that we now have a delivery format that’s compatible with a much wider range of consumer devices. It’s imperfect, as we’ve discussed, but it is much more easily-consumable. So now that labels and artists know their listeners can hear the music in this format, they’re more open to exploring the creative possibilities. That’s what really has me excited about this–it has the potential to rethink how we do everything in the music business. So I’m thrilled with where we are, but even more excited about where we’re going.