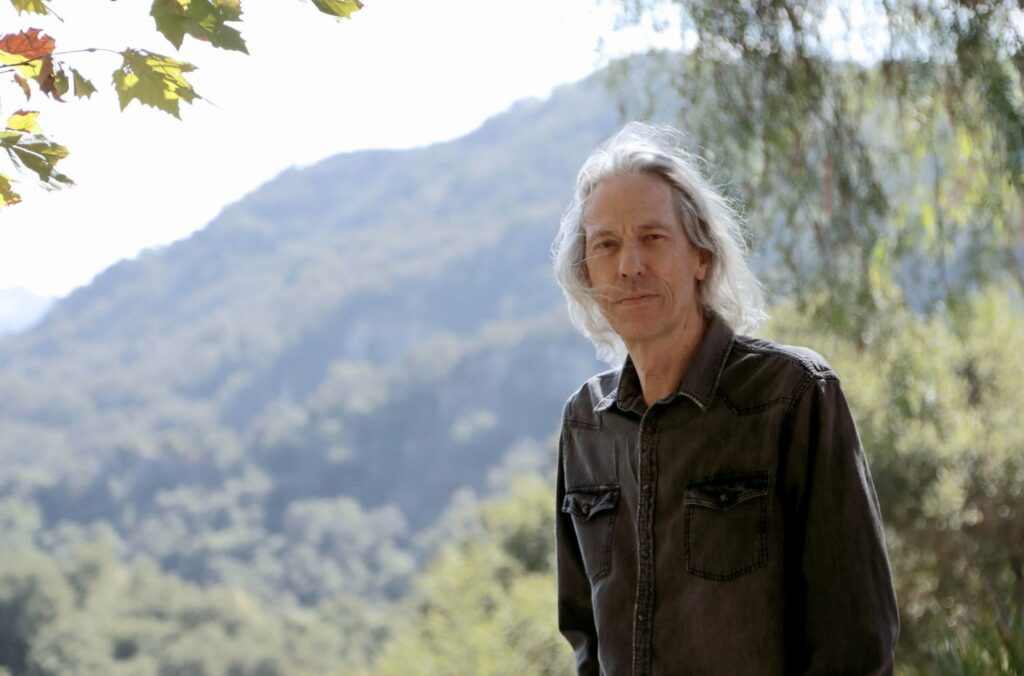

Ryan Ulyate has been recording, mixing and producing music professionally since 1978. In 2005, he began a decade-long collaboration with Tom Petty that included mix and production credits on the Mojo (2010) and Hypnotic Eye (2014) studio albums.

He’s also a big proponent of immersive and high-resolution audio, having created 5.1 surround sound mixes of the aforementioned two albums as well as Damn The Torpedoes (1979) for the now out-of-print High Fidelity Pure Audio Blu-Ray editions. In 2020, he upgraded his Topanga-based studio for Dolby Atmos monitoring and has since mixed Petty’s Wildflowers (1994), Angel Dream (1996), and Greatest Hits (1993) records in the new format.

Ulyate’s latest project is Act 3, his debut album as a solo artist. Inspired by the bands he listened to while growing up, as well as artists he’s worked with, it’s a tapestry of classic British and California rock. As of this writing, the album is exclusively available as a high-resolution immersive download through IAA’s online shop. The Dolby Atmos mix was created by Ulyate himself and mastered by Michael Romanowski at Coast Mastering. In November 2023, Act 3 was nominated for the Grammy for Best Immersive Audio Album!

Based on his love for conceptual works like The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) and Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and produced especially for Dolby Atmos, Act 3 is designed to take the listener on a 45-minute immersive audio journey while also making some observations about the world we’re living in from the perspective of someone who grew up in the “Dreamland” of California.

I recently had the chance to catch up with Ryan about the making of Act 3, his newly-released Dolby Atmos remix of Mojo, and more!

You’ve been working as an engineer and producer for decades now, but this is your debut release as a solo artist. What made you want to finally want to do your own record?

Since I first started engineering, I was always dabbling in songwriting on the side. I got my foot in the door at a studio and worked my way up to chief engineer at 21, so I’d come in during downtime to record my own demos. Back then, I managed to get a meeting with Herb Alpert of all people!

Herb was interested in what I was doing and wanted to develop it further, but I kind of dropped the ball. [laughs] I was working so hard as an engineer at the time, and it seemed like a big risk to put that on hold and try to make it as a musician instead. So I decided to stay on the engineering path, but this stuff has always remained there in the background.

Now that I finally have a bit of free time, I realized “if I don't do this now, when am I going to do it?” So here we are.

Were all the songs written recently, or have you been stockpiling melodies and lyrics for some time now?

The chords and melodies for some of them have been around for ages. Sometimes I’d have a lyric, but most of them came during the last three years or so in dreams.

For example, the whole melody of “Drink Up” came to me in a dream. I'd wake up and kind of mumble into my phone what I heard, then try to figure out what the chords were and sing the melody. Sometimes I’d go down to the piano and try to work it out there. I must have at least a hundred or so of these little song snippets in my phone.

So, so many of these things came from dreams. Another one, “Game Of Hope,” came from a dream I had about Tom Petty not long after he died. We were in a guitar shop together, and he started playing the chord progression on a Rickenbacker. Then, it cuts to another scene and we’re driving down central valley in a pickup. He looks at me and says “you could call it ‘Game Of Hope’.” So he gave me the title and the chords for that song in the dream. Absolutely crazy.

To make the album, I’d go back through all these little snippets and look for anything that was good. If it needed a chorus, I'd work on that next. Then after all that, you’ve got to figure out what the words are and what the song’s about. That’s the hardest part, deciding what I was going to say as a songwriter. The biggest challenge was probably coming up with lyrics that didn’t make me feel embarrassed. [laughs]

Coming up with the melodies and chord changes is great fun–I could do that all day–but trying to say something that’s eloquent and has real meaning is so difficult. I worked really hard at it, and I feel good about the result.

Though it’s made up entirely of original compositions, you’ve described Act 3 as a “tapestry of classic British and California rock.”

Yeah, I'm proud of the fact that it’s an homage to all that music. I definitely wear my influences on my sleeve. The funny thing is, sometimes I don’t realize it's reminiscent of all that until I’m listening back to the finished tracks.

I always thought of myself as more of a prog rock guy, but all of a sudden I’m hearing Beach Boys stuff in these songs. I didn't think I was a Beach Boys fan, but everyone loves “Good Vibrations” and Pet Sounds.

The biggest reason why I’m so proud of this album is the musicians that play on it. You’ve got Steve Ferrone on the drums, who’s just so brilliant and powerful. With him, there’s not one drum hit that’s out-of-place or doesn’t completely serve the song. It’s just simple and direct, and he’s so good at it.

The other person who really shines on this album is Josh Jové, who’s the guitarist for a band called The Shelters that Tom Petty and I produced. I remembered from working with them what an amazing guitarist he was. We went just nuts on this album with the guitar parts. I knew I was going to mix it in Atmos, so I wanted to have things constantly happening all around and lots of ‘ear candy’.

Yeah, I definitely hear some Beach Boys harmonies in the opening track “Dreamland.”

When we started working on what became “Dreamland,” I didn’t even have a lyric yet. There was a pretty basic backing track of me just playing chords on keyboards and bass. Josh came in and started playing all these surf guitar riffs, with the whammy bar and all that stuff. He also came up with that cool little Hawaiian-sounding coda at the end.

I’m sitting there thinking “this is great! We’ll make it a ridiculous surf rock track.” So when it came time to write the lyrics, I decided to make it about the “California story.”

Everyone has a California song: “Hotel California,” “California Dreamin,” etc. So it ended up being my California story, which is so fun, but in the end it was the guitar that really inspired the lyric.

I mentioned this before, but those guitar harmonies in the height speakers throughout “Drink Up” really reminded me of Brian May’s playing on the classic Queen records.

Yeah, that was completely on purpose. We were totally willing to go there.

I think that’s really part of the fun of the album, that I wasn’t afraid to dive into those places and just hang out there. I just love all that music, and it’s a fun tip of the hat.

Did you track the album the old-fashioned way with all the musicians playing together in the same room, or was it built up in stages by overdubbing?

I started with demos that had basic kick-snare rhythm patterns and chord structures. I played bass on those, but I’m a really bad bass player so there was a lot of editing there. [laughs] Ultimately, I got what I wanted and the structure was pretty solid.

Next, Josh came in and added all sorts of guitar parts. Then I brought Ferrone in and he kind of made his own notes. He has his own way of notating stuff. After the drum parts were finalized, Josh might have come back and done a few more things if we were missing things here and there. Then I had to wait for this singer who took forever. [laughs]

The biggest reason why I’m so proud of this album is the musicians that play on it. You’ve got Steve Ferrone on the drums, who’s just so brilliant and powerful. With him, there’s not one drum hit that’s out-of-place or doesn’t completely serve the song. It’s just simple and direct, and he’s so good at it.

For me, one of the standout elements in the album are the harmony vocals. They’re so elaborately-constructed and sound amazing spread out into all the different speakers. It almost reminded me of some of the best tracks that Jeff Lynne produced for The Heartbreakers, like “Free Fallin’” or “Into The Great Wide Open.”

Yeah, that’s the fun thing about making records. Once you get going, you can start layering up all these extra parts and doubling things to make it sound really big. I just love that over-the-top kind of production. In “Play On,” there’s this big chorus-y vocal part that comes in and I’m definitely tipping my cap to Jeff there.

I want to make something that’s fun to listen to, but also slowly presents itself over repeat listens. You might pick up on something new the eighth time you hear it that you may have missed the first time. You know what I mean? It’s all about throwing a lot of subtle little things in there to grab your ear, and it's so fun.

In the song “Shiny New Conspiracy,” there’s a ‘da-da-da’ background vocal part that totally sounds like The Turtles. It’s “Happy Together,” you know? I just couldn't resist throwing in fun little things like that.

I never would have guessed that the drums were the last instrument to be tracked. In some ways, that goes against everything I’ve been taught about studio recording.

Absolutely, but that’s how I had to do it. I recorded everything at my house, and I don’t really have the space to do a full-on old school tracking session. Plus, to be completely honest with you, I didn’t really know the full construction of the songs yet either. When you have everything laid out in MIDI, you can kind of tweak things and make changes to the arrangement as you go.

So you booked a studio to do the drum tracks with Ferrone?

No, the drums were done in my living room!

At the house here, I’ve got this big room with 22-foot ceilings. When we had the garden re-landscaped, I had the contractors dig a trench and run snake cable from the studio down to the house. So I’ve got 24 mic lines going to that room and a collection of mics to choose from right here.

The living room has a nice reverberant quality, so I used a lot of ambience mics which you can hear in the back channels on the Atmos mix. I love having that ‘room sound’ because it really puts you in the space with the drums. Even with the older Tom Petty recordings I’ve been remixing in Atmos, the engineers who worked on that stuff like Jim Scott would always put up room mics on the drums.

You can really hear it on the Wildflowers album, especially “You Don’t Know How It Feels.”

Yes! That was the first track I ever mixed in Atmos, and it worked out so well.

Throughout, the drums sound so clear and natural. You really get that dynamic ‘punch’ and power without the harshness that comes from being too reliant on bus compression.

Yeah, I really stopped doing that compressed drum thing while working with Tom Petty on the Mudcrutch stuff and then Mojo. It really takes all the meat out of the drums, especially when you have a great player like Ferrone. You don’t really need to do much, except just get out of the way.

You mentioned that Act 3 was written and recorded with Dolby Atmos in mind. Can you think of any specific moments or passages in the album that really take advantage of the format?

“This Is How It Ends” gets really dense in terms of the guitar layering at the end. There’s a main riff, an answer riff, then these other guitars that are sustaining and kind of building tension in the background.

All these parts would blend together in stereo, but here you can have the main riff on the bottom level, the answer up top, and then the sustaining thing kind of arching around the entire space. It shows what the medium is really capable of. You can have this interesting density that’s not necessarily appreciable in stereo.

“Play On” has a lot of really interesting things on it too. There’s an acoustic guitar that does the fills and melodies, but we also had Josh double that part with two fuzzy-sounding electric guitars. I put the fuzzy part behind you in the heights, so it adds an extra bit of dimension to the piece.

One of the best examples for me is in the beginning of “Game Of Hope.” It starts off with the ticking clock sound panning rear to front in the heights, then you’re bringing in a different pair of speakers with each element as it builds: bass in the fronts, rhythm guitars in the sides, and then the whole thing takes off with the drums all around and vocal in the center. It’s so cool how you can play with the size of the soundstage during moments like this to build tension and excitement.

Yeah, that's a fun one. It was kind of designed to do that. You start off with something simple, then build it up or reduce it back down again to keep things interesting.

There’s also all those little sound effects at the beginning and end of the songs. It’s another homage to the classic albums I loved, bands like Pink Floyd would use these kinds of soundscape things to put the listener in a certain mood before the song started. I wanted this project to be something you could experience as an album, not just a collection of disconnected songs.

The other person who really shines on this album is Josh Jové, who’s the guitarist for a band called The Shelters that Tom Petty and I produced. I remembered from working with them what an amazing guitarist he was. We went just nuts on this album with the guitar parts. I knew I was going to mix it in Atmos, so I wanted to have things constantly happening all around and lots of ‘ear candy’.

The thunderstorm sounds traveling overhead at the beginning of “After The Fall” definitely made me think of The Doors’ “Riders On The Storm.”

We don’t usually get thunderstorms in Los Angeles, but there was a really weird one last summer. I opened the front door and took out my little Tascam recorder, and that’s where that big thunder crack came from. The song “Home” also incorporates streams and other nature sounds from Topanga, which is all just part of my everyday world.

There’s an old Pink Floyd sound called “Grantchester Meadows.” It’s a Roger Waters composition from the Ummagumma album, and it starts off with all these natural sounds of birds and flowing water. Being an old diehard Pink Floyd fan, it was so fun to pay homage to that stuff.

Like you said, there’s definitely another Floyd reference in the song “Home” with the piano. My buddy Steve Rucker played that part, which I ran through a Leslie speaker to get that ‘watery’ effect.

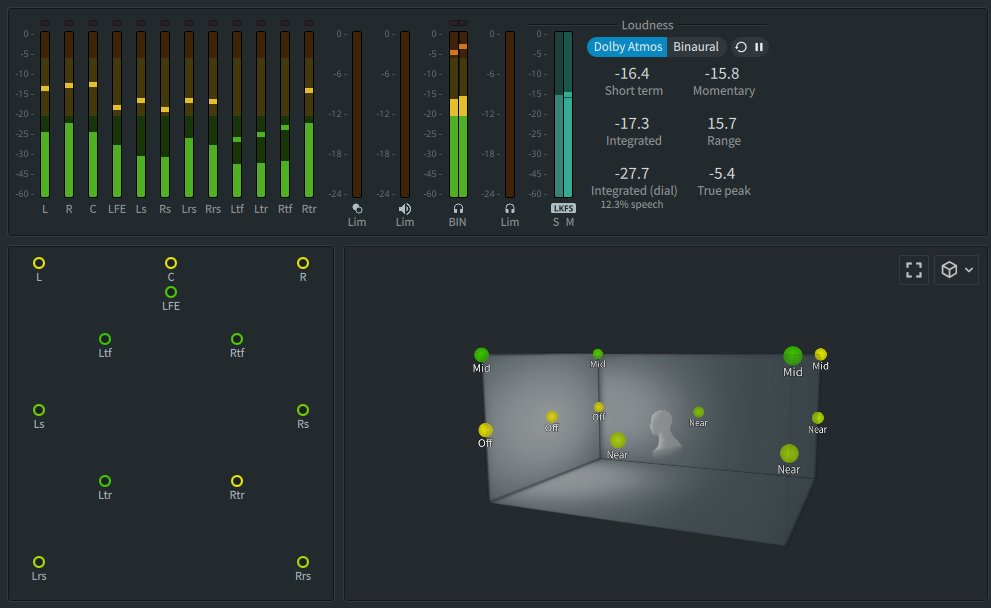

Looking at the masters you sent through the Dolby Atmos Renderer’s display, one thing I couldn’t figure out was how you were able to create movement in the height speaker array (like with the guitar at the end of “This Is How It Ends”) even though all the objects were stationary.

Yeah, I have a really simple way of working. There’s four stationary objects in the top corners, which I have a sub-mix pointed to. Then I’ll just use a quad panner inside Pro-Tools.

When I started working in Atmos with the Tom Petty catalog, I made the decision not to do a lot of gymnastics and flying things around. I didn't want to distract people. When the music’s really good, I think all you have to do is put the listener inside of it. You don’t have to do crazy stuff because the excitement and dynamics are already present in the orchestration.

The new Dolby Atmos “Extra Mojo Version” of Mojo just came out on the streaming services. As the original producer and engineer, what was it like revising those tracks more than a decade later?

Yeah, we cut most of it in 2009 and it came out in the Summer of 2010. We’d just turned The Clubhouse–which was their rehearsal place in the valley, where they stored all their guitars and gear–into a studio.

The entire thing was basically done like a live show in the studio, using monitor wedges instead of headphones. We had a great monitor mixer named Greg Looper who's not with us anymore sadly, he was a lovely guy.

When you're recording basic tracks in the studio, it's so important that the band hear and react based on each other’s performances. As an engineer, your job is sometimes as simple as just capturing everything and making sure everyone can hear each other. Since there were no headphone boxes and a dedicated live mixer was giving them the mix, all I had to focus on was capturing the audio.

Digidesign (now Avid) had come out with this new live mixing board, where you could take everything that came from the stage mics and pass it straight into a Pro Tools rig. So I could be sitting in the control room, listening to and working on this stuff as it came in while they were still tracking.

For the band, it was more like rehearsing than making a record. That casual, looser feel comes through so well on the album. It’s the sound of people in the same room really listening to each other and always going for the best take–because if the guitar solo isn’t good, too bad because you’ll hear the bleed in every mic. [laughs]

In Atmos, it works really well because everyone’s in the same room at the same time. As you spread things around, the bleed kind of works in your favor and puts the listener more in the room.

Despite the way it was recorded, there’s so much separation in the Atmos mix. On a few of the songs, like “Running Man’s Bible” and “The Trip To Pirate’s Cove,” you can hear Mike Campbell’s guitar leads coming almost entirely from the front left height speaker

When it came to working on it, there really weren’t any rules. If a song warranted heavy use of echo and delay, we’d just do it. “Pirate’s Cove” was great fun in that regard. I remember spending days on it, with at least six different delays set up in the session.

The great thing about working in-the-box is that when it comes time to do an Atmos mix, all you have to do is open all the original Pro-Tools sessions and everything’s laid out. Fortunately, I still had the Pro Tools rig that was used to record the album and had frozen it around 2013 or so.

Any chance you might be asked to mix Hypnotic Eye in Atmos too? “Shadow People” ranks among my favorite Heartbreakers tunes.

I listened back to the 5.1 version recently, and there’s a song called “Power Drunk” that has this awesome backwards echo on the guitar. It’s that old trick I learned from Jimmy Page: you take the guitar and play it in reverse, then add reverb into it and reverse that again.

So you end up with reverb that happens before the dry sound, creating a sort of ‘backwards’ effect. Led Zeppelin used that effect all the time, like in “When The Levee Breaks” and “You Shook Me Baby” from the first album.

Since it works so well in 5.1, I think Hypnotic Eye would be great in Atmos too. There’s always hope! [laughs]

Nominate Act 3 (Immersive Edition) for IAA’s 2024 Listener’s Choice Award!