Throughout his decades-long career, British artist, producer, and engineer David Kosten has collaborated with a variety of artists including Keane, Everything Everything, Bat For Lashes, and Steven Wilson. Since 1999, He’s also released music of his own under the name Faultline. The second Faultline album, 2002’s Your Love Means Everything featured guest vocal contributions from Coldplay's Chris Martin, R.E.M's Michael Stipe, and The Flaming Lips.

In 2023, Kosten was tasked with creating brand-new stereo and Dolby Atmos mixes of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells as part of celebrations surrounding the iconic album’s 50th anniversary. These remixes were included on a limited-edition Pure Audio Blu-Ray sold exclusively via SuperDeluxeEdition.com. Since then, he’s completed two more vintage album remixes in Atmos–Paul Young’s No Parlez (1983), and Keane’s Hopes and Fears (2004)–both of which also received Blu-Ray Audio releases from SDE.

I recently had the chance to chat with David about his immersive audio journey, the complexities involved with rebuilding classic albums from the original multitrack tapes, and where he thinks the industry is headed.

How did you first get into audio engineering and mixing? What drew you into this niche world of immersive audio and remixing classic records?

I've been producing records for 20 years now, and even before then I was making music as an artist myself. I couldn't be doing any of what I do with immersive audio now without those experiences of making my own records, producing and mixing other people’s music, and observing engineers at work.

These vintage remix projects require a very specific set of skills. The bulk of the work I do goes into exacting recreations of the original stereo mixes before breaking the individual elements out into the immersive space. So while I know I’ve come into this relatively new area at quite a decent level, getting to work on these classic records, I spent a ton of time making sure I was up to the task and responsibility. I also think clients recognize that I'm high up on the obsessive scale when it comes to reproducing all those finer details and won’t let them down [laughs].

Before I started working in this field, I listened to a lot of Atmos mixes of classic records to get an idea of what other people were doing. They didn’t always sound the same as the originals mix-wise, which drove me crazy. Those records were made by brilliant artists and engineers, all of whom spent a lot of time getting the final mix result to sound just the way they wanted. As a fan, I don’t want somebody else to remix it and change it. I just want to hear the original sound spread across multiple speakers, as if they had made multiple stems at the time!

Unless the goal of the project from the start is to radically change the sound, it’s mostly about trying to closely recreate the original mixes and not mess too much with listeners’ memories. All the tiny details are vitally important, I think.

I completely agree. It's so disappointing when an immersive interpretation of a classic album fails to live up the original stereo mix, especially since it’s unlikely that the artist or label will devote resources toward having that record remixed again.

I’m sure you’ve listened to dozens more Atmos mixes than I have at this point, since you’re writing about them. There are so many being released, but I do wonder how often other mixers are given the proper resources and time to really put in their very best work. As you probably know, the budgets aren’t always there for these types of projects. You might only have a week to turn in an album.

In the case of Sophie Ellis-Bextor's “Murder On The Dancefloor,” I only had a couple of days to hand in the Atmos mix. But the great (and lucky) thing about that track is how brilliantly-produced it was–once I started pulling up faders and recreating the balances, it sounded extremely close to the finished version. The only real trickiness was that they’d flown in bits and pieces from the demo vocal performance, so I got hold of the original multitrack of the demo and dropped in those few words in order to make it match.

It’s just so cool being able to sort of tell the story of a classic album using this immersive format. I can’t give anything other than 1000% to it or I feel like I’m letting the artist and their fans down.

I first became aware of you through your work on Steven Wilson’s The Future Bites. How did you and Steven become acquainted? What did your role as producer on this project entail?

We have to go way back to the early-90s, when Steven was making records in a group called No-Man. I totally loved what they were doing, and they were working with musicians that I’d been obsessed with too–members of the band Japan.

I had placed an advert looking for a singer, and a guy who turned up was lovely–but we weren’t right for each other musically. He recommended that I check out No-Man’s music, and I got excited since I was already a fan. He also said he was friends with the singer, Tim Bowness, and knew Steven as well. So through him, I met Tim who in turn introduced me to Steven–and that was nearly 30 years ago now.

Steven and I kept in touch and met up a few times over the years, but I didn’t particularly connect with the music he was making at the time and he knew that! One day though, he called me and said "I’ve made some music you might actually not hate.” So he sent me his new tracks, which I loved, and those were the demos for The Future Bites! He’d never worked with a producer before, so we did a trial song–”King Ghost”–just to see how we got on and it worked out really well.

One of the best songs on the record, I think.

Yeah, I did a lot of programming on that track and was super happy with how it turned out. It came together really quickly and established a great working method between us.

Steven is an exceptional writer, producer and engineer, so the working dynamic was very different than if I was working with say a singer that didn’t also compose or produce. It was much more of a collaborative effort, where he already had the songs written and then I’d come in with additional ideas or suggestions. We also tracked all his vocals here at my studio and I’m very particular about vocal direction, so I think that made an impact in itself.

You guys worked on so many songs during this period. There’s almost an entire second album’s worth of additional material included in the deluxe edition, as well as extended versions of some tracks like “Personal Shopper” and “Eminent Sleaze.”

I probably only worked on 10 or 11 tracks total, so I wasn’t involved in all of that. With “Personal Shopper,” my main contributions were recording the live drums and also helping shape the Elton John voiceover section. Steven knew what he wanted Elton to say, and then I turned it into this big cacophony of sound.

That’s one of the most fun passages in the album, especially in the Atmos mix.

Yeah, it couldn’t have been more perfect for that. There’s the singular voice–what’s actually being said–and then all these other voices showing what’s going on inside your head.

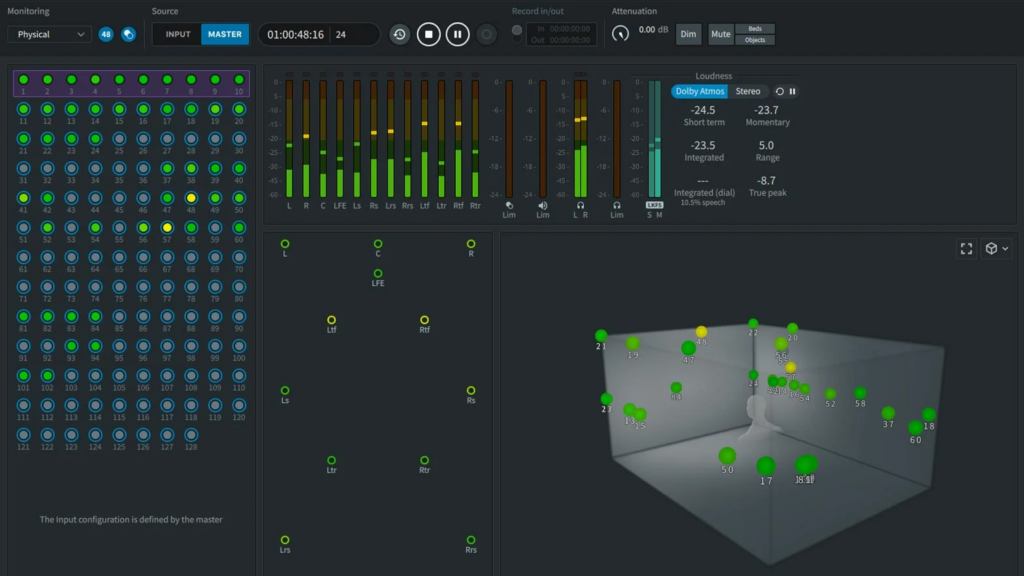

That was a big moment for me, because we went to Dolby’s facility in Soho Square to do the Atmos mix. It was the first time Steven had worked in Atmos, and my first experience of hearing music in an immersive format. I thought it was so amazing.

Even though I had mixed The Future Bites in stereo and created all the stems used to make the immersive mix, that session was a real eye-opener for me. I knew I needed to be able to do this in my own studio, because so much of my own music would be ideally suited to the format.

I wouldn’t have guessed that The Future Bites was mixed from stems. Generating those must have been quite a time-consuming process, since you need a lot of seperation really get the most out of the format.

It took a while. I can’t remember exactly what I did, but it was definitely comprehensive and varied per song. Thinking back now, there may have been a few tracks where Steven asked me for more separation and more elements.

Most Atmos mixers seem to be working with stems, and I think a big issue with that approach is they’re not being given enough separate elements. In an 11-speaker environment, what can you really do with a stereo stem of the entire drum kit with all the reverb and compression baked in?

I’ve certainly dealt with this, most recently with Keane’s Hopes and Fears. For that job, I was asked to use a combination of original stems as well as going back to the multitracks.

I’m sure there are engineers out there being asked to create Atmos mixes using just a handful of stems with instruments already combined. When it comes to albums from the ‘90s and early-2000s, when digital recording was happening via computer for the first time, you would have had to print those stems individually in real-time. Today, it’s all done at the push of a button at high-speed.

I always thought that Hopes and Fears was a relatively simple production in the sense that there aren’t that many instruments in play. It seems like the core elements are a single vocal, drums, and piano, but your Atmos mix reveals all kinds of hidden layers that I wouldn’t have guessed were there.

A big part of the record is definitely Tim [Rice-Oxley] getting that classic piano sound with his CP-70, but the genius is in how he created these final layers of sound. Though it mostly feels like one thing in stereo, there are actually 17 different keyboard parts in my session for “Somewhere Only We Know.”

There are single notes on octaves in particular places, or these synth parts that are synchronized to the piano really well–so you get a sort of fluid drift-like quality to the sound, with the chords bleeding on top of each other. Then there are these rhythmic sequencer parts tucked in there, which help fill in the gaps and glue everything together.

Spike Stent did an incredible job mixing this record. There are a lot of subtle level rides happening, and some really lovely dynamic changes especially around the vocals. I went to see them play at the O2 this past Friday night, 20 years to the day that Hopes and Fears was released. Who could have imagined that two decades later, they'd be playing those same songs to a crowd of 20,000 fans?

Last year, you had the opportunity to create new 50th anniversary stereo & Dolby Atmos mixes of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells (1973). How did you come to be involved in this project? How difficult was it to re-create the balances and processing used in the 1973 mix?

Tubular Bells was recorded on 2-inch 16-track tape, and every second of that multitrack was crammed full of information. I had never seen anything quite like it. There isn’t a single tape track that stays as one sound throughout the pieces. On average, it was maybe five or six sounds per track. For Part One alone, I must have made around 120 stems in order to do the Atmos mix. If I'd been given a year to mix it, I honestly could have used that time [laughs].

As for how the project came together, I think the label’s original plan for the 50th anniversary was to reissue the 5.1 mix Mike had done some years ago. I was just starting to learn this craft the previous year and Caroline Hilton–who oversees a lot of the Atmos work they’re doing at Universal–was so helpful in giving me advice and critiquing early mixes I’d done. Eventually I got to the point where she was really impressed with what I was doing.

Not long after that, I got a message asking if I was interested in remixing Tubular Bells. I think this was in February of last year, then I had to deliver it at some point in March. So there wasn’t all that much time to handle a project of this enormity, and I had the huge responsibility of doing justice to such an iconic record. I basically didn’t leave the studio during that time [laughs].

In a way it’s the perfect record for Atmos, because it’s this big sound collage of intertwining and overlapping parts. It doesn't sound like a real band performing on stage, so there’s no need to go for a realistic perspective with the spatial mix.

Yeah, exactly. If you listen to it on a nice playback system, it really does give the feeling that you’re surrounded by Mike Oldfield playing all these different parts. It’s crazy to think that he was only 19 when he recorded the album, and a lot of performances were single takes.

I had actually finished the Atmos mixes of both pieces, then ended up scrapping those and starting afresh as I knew I could make it hang together in a more satisfying way. Especially with longer compositions like this, it's easy to make the whole thing just feel like a collection of parts that don't really sit together well. It’s also tempting to spin things around and put sounds in all sorts of crazy places, but I found doing that made me lose the feeling of being totally embedded in the music.

People have been trying to come up with rules and guidelines for mixing in these spatial formats like 5.1 and Atmos for years now, but at the end of the day the mix has to fit the song. For instance, on some tracks you can get away with really pulling apart the lead and harmony vocals to create a big room-filling chorus. In other cases, certain elements have to stay together or the results can be too revealing. Just because you have the ability to place something behind or above the listener doesn’t necessarily mean you should.

Yeah, I agree. When you hear something coming from way over there or behind you, there has to be a decent reason for it. It probably shouldn’t just wave at you saying, ‘hey, I’m a fun gimmick.’ If you go to the last ten minutes or so of Tubular Bells Part One, there’s that whole section where Vivian Stanshall is introducing the ‘orchestra’ as master of ceremonies. Each instrument starts only in the left channel, then moves across the stereo image over to the right as it’s playing. By the time one part is in your right ear, the next one is already coming in on the left. It’s sort of like a parade or a procession.

In recreating the original ’73 stereo mixes, I was pretty obsessive in tracking those patterns so they start and end in the exact same place. I decided I would much rather honor Mike Oldfield’s original decisions and creativity.

Another consideration is how the Atmos mix is being released. With “Murder On The Dancefloor”–which is streaming only–I found that particularly with the percussive sounds, the way I was placing things on speakers didn’t always translate to binaural in a way that was predictable. So I did change my approach a bit for that one, because it’s such a famous song and I wanted to make sure the headphone rendering didn’t sound too different from what people are used to.

On the other hand, with Paul Young I was told from the start that it was only being released on a physical product and not DSPs–so I should mix with that in mind. The comments I’ve seen about that one have all been very positive, and I think a lot of that had to do with me not having to worry about making sure it sounded right binaurally on headphones.

This is something I’ve struggled with since immersive streaming first launched a few years ago, because I know that headphone compatibility is ultimately what’s driving the labels to invest in the creation of more Atmos mixes. That being said, you and I both know that it’s simply no comparison to a good speaker system.

For sure. I know most people aren’t going to have a full-blown 7.1.4 Atmos system in their house, but I recently got a Sonos ERA-300 speaker. It’s just one device with lots of speakers built-in, but it plays Atmos tracks and the result is definitely wider and deeper than stereo.

One solution to the translation issue maybe is to do two different mixes, one intended just for speakers and the other optimized for headphones. That said, I imagine not many labels will accept two unique Atmos submissions for the same album! But there really is a difference when you’re mixing just for speakers, and it would be great to make decisions in that environment without having to worry about headphone compatibility.

Of the three vintage projects you’ve completed thus far, I imagine Tubular Bells was probably the most difficult to rebuild.

It wasn’t! As insanely complex as Tubular Bells was, Paul Young’s No Parlez actually beat it.

I wouldn’t have guessed that! I know that Paul Sinclair was very much a driving force in bringing that project to life. I’m guessing he was the one who approached you about remixing No Parlez?

Yeah, I already knew Paul from when SDE released the Blu-Ray edition of Tubular Bells. I was familiar with some of the music on No Parlez, but I asked them to send the multitracks just to see what I was getting into.

I thought I had done my homework in figuring out what might be involved in recreating the mixes, but it turned out that the guys who mixed No Parlez were just as fader, EQ, and effects-happy as Mike Oldfield! In every single one of those songs, nothing stayed the same for more than a few bars at a time.

Out of the 14 songs I mixed for the Blu-Ray, there were only one or two where I didn’t have to radically chop up the multitrack in order to piece together the final mixes. In terms of the structure of the songs, what was on the actual tapes had almost no resemblance to the final versions.

I wasn’t familiar with the album, but when the Blu-Ray was announced I did start listening to the stereo mixes on Spotify to get a feel for the material. One thing I noticed immediately is that the first song “Come Back and Stay” has an extended intro in your Atmos mix.

It turned out there were unique mixes made for the LP and CD editions of No Parlez. They wanted me to recreate the LP mixes, so there were times when I’d be hunting through a three-minute drum outro trying to find that one fill that was actually used on the LP edit. There was also work using AI to help replace missing bits of vocals here and there. So it was definitely another level up in difficulty from Tubular Bells, mostly because of all those edits and missing parts.

When the original stereo mix was done back in ‘83, they were acting almost like live remixers–flying in echoes and all kinds of other effects that weren’t on the multitrack. The tapes only have raw sounds, so it was really tricky to figure out how they did some of those things you hear in the final mixes. Even some of those Simmons drum sounds, which the entire record is built on, seem to have been triggered live at the mix since they weren’t on the tapes.

So what you’re saying is that in the control room in 1983, there was an assistant engineer manually operating a percussion sampler (something like a CR-78) live to the two-track mix? It’s amazing to think records used to be made that way.

Yeah, I reckon so. It made me think back to some of the very first recordings I ever did, back in 1984 at age 15. I remember the engineer said he could improve my snare sound by routing it into this new pedal he had, which triggered a clap sound effect every time the snare went through it. The Paul Young album has a lot of that same clap sound, so maybe that’s what they were doing at the time. The sound would change depending on how loud the signal you flew into it was, so there must have been some kind of envelope filter in there.

No Parlez was produced by Laurie Latham, who I was a huge fan of as a teenager. Both he and Paul Young were very well-educated in production techniques, and their influences at the time were artists like Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, King Sunny Adé, and of course Bowie. I think a lot of people only know the hit singles, but there is some really cool experimental stuff going on across the whole record.

I met Laurie at the playback we held for the Atmos mix back in March, and he was amazed that I even copied all the times when the reverb cuts off at the multitrack edit points–because the echo suddenly stops when you cut the tape. There are a lot of spots on the record where this happens with no crossfade, so I had to match it.

One aspect of the No Parlez Atmos mix I thought was especially interesting was the way you used the center speaker. Rather than feature Paul Young’s vocals, it’s engaged almost exclusively for Pino Palladino’s fretless bass. What made you decide to utilize the center in this unorthodox way?

Since I’m just starting out, I really wanted to reduce risk and make sure the final mix balance translates to listeners’ systems as predictably as possible. I’m not yet a huge fan of having a dry vocal in the center speaker either. Plus, there are some spots in the Paul Young record where his voice moves around in stereo a bit and I wanted to bake those movements into the finished playback.

The album is really famous for three things: the fretless bass, Paul Young’s ridiculously-awesome singing, and those amazing backing vocalists. I think they were called “The Fabulous Wealthy Tarts?”

That's the best part of the album for me! Those backing vocals are wild.

Yeah, they’re extraordinary. So playful and inventive, and fundamental to the sound of the album. When I was going through the multitrack piecing the album together, it was so important to find all those parts. In some cases they weren’t there at all, and I had to do some trickery like extracting them from the stereo mix.

How do you explain that? Could they have punched in some of those vocal parts live to the two-track mix?

Crazier things have happened. Like with Mike Oldfield, the Tubular Bells at the end of Part One actually weren’t on the multitrack. I heard that another engineer persuaded him to erase and re-record them, because the original sound on the record had distorted. It’s amazing to think someone would go back to the original multitrack of a multi-million selling record and erase parts of it, but that’s apparently what happened. To get the original sound back into the Atmos mix, I was able to extract it from the quarter-inch stereo master.

In Tubular Bells Part Two, there was an entire passage–the “caveman” section–that wasn’t part of the initial set of multitrack transfers they sent me. This incredibly helpful guy working over at Universal’s archive spent weeks looking for that missing tape, and found it on the day I was meant to hand the mixes in. So the Atmos mix went from being 22 minutes to 24 minutes, but I think there were still four or so bars where I had to cut to the stereo mix as we didn’t have the materials on the multitrack.

So before the drums kick in fully with a caveman shouting, there's a few seconds of just using the original stereo and then it cuts back to the multitrack. It’s probably not so noticeable on headphones, but on speakers you might find everything suddenly moves to the front and then pulls back out again.

I suppose no one ever thought they’d have to use these multitrack tapes again. With Keane, I imagine there were different challenges with reassembling the multitrack because it was recorded digitally?

Yes, it was an early Pro-Tools session. The files didn’t open at first, so I contacted a company that specializes in transfers of old DAW sessions. They told me my only option was to go buy an old computer with the proper OS, which just wasn’t going to happen! Then, this same awesome guy who worked at the Universal Archive said he had a contact in The States who specialized in this sort of thing.

They sent me some convoluted instructions for how to open the 2004 session on my current rig, but amazingly it all worked. Even the plugins they used at the time, like Line 6’s Echo Farm, all loaded up with the right settings. So you can imagine my glee in discovering that a huge amount of extra rebuild work didn't need to be done.

Spike Stent mixed the album on an SSL console, so there was still a lot of work to be done in recreating fader moves and outboard EQ. It seems like they did some basic EQ in the session, and then more on the console.

I imagine they also used the famous SSL bus compressor in the console to process the entire two-track mix.

Yeah, exactly. I wanted to recreate all that sort of stuff, but not the brickwall limiting done to the original stereos. In addition to doing the Atmos mix, I also helped with the remastering of the original stereo version and we dialed back a lot of that.

I wouldn’t convince anyone to go with no compression or limiting–I think the band understood that it added something cool to their sound. It gives a sort of relentless excitement to the louder tracks, but there’s definitely a few dBs more breathing room in the remaster–and even more so in the Atmos mix.

Can you tease any other immersive projects you’re working on? You already mentioned “Murder On The Dancefloor,” which I had no idea existed until now.

Not really, but there are some conversations going on that are really exciting. I can’t believe I’m getting the opportunity to work on some of this music.

If you could remix any older record in Atmos, which would you choose?

It’s a tricky question because it’d be so cool to work on some of my favorite music–albums like The Human League’s Dare! (1981) or Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden (1988)–but at the same time, I almost don’t want to put that kind of pressure on myself.

That said, I’ve definitely been emboldened working on these three classic records that people really love–so I'm kind of in a place now where I can tackle pretty much anything and feel good about it.