Ken Caillat is best known for producing and engineering the Fleetwood Mac albums Rumours (1977), Tusk (1979), Live (1980), and Mirage (1982), along with his daughter Colbie Caillat's Coco (2007), Breakthrough (2009), All of You (2011), and Christmas In The Sand (2012). Ken's recordings have sold over 50 million copies. His record production and engineering efforts earned him numerous Grammy nominations, including an Album of the Year Grammy and Best Engineered Album. In 1997, Caillat founded 5.1 Entertainment and has mixed more than 200 songs in 5.1 surround for artists such as Billy Idol, Frank Sinatra, Pat Benatar, the Beach Boys and Fleetwood Mac.

Claus Trelby has worked as Engineer, Producer, Chief Engineer and Director of Technology for 30 years, on projects involving Music Production and Digital Archiving/Preservation efforts. He has worked directly with artists such as Bette Midler, Rancid, Herbie Hancock, Peter Frampton, Eric Clapton, Sting, and Dishwalla. He was nominated for an Emmy for his work on Sting's All This Time project. Claus supports all surround and spatial music efforts due to his love of immersive audio.

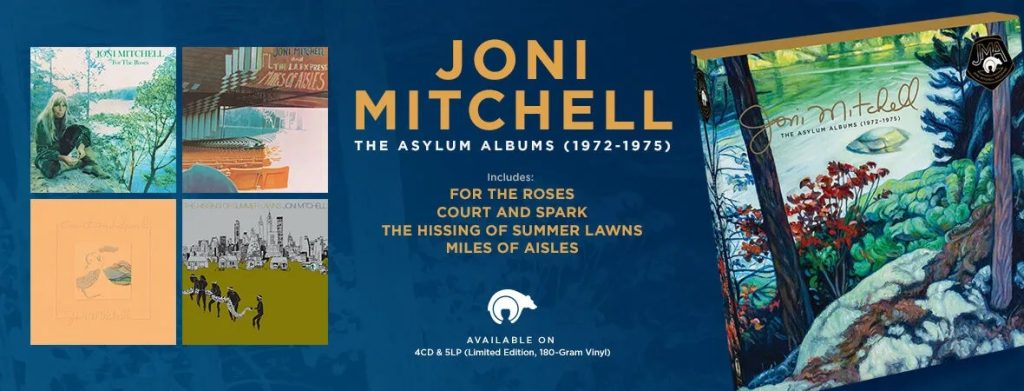

Ken and Claus recently had the opportunity to remix four classic Joni Mitchell albums from the mid-1970s in Dolby Atmos–earning them a nomination for IAA’s 2024 Listener’s Choice Award–along with her 2022 comeback performance at the Newport Jazz Festival.

I recently had the chance to chat with both men about their Atmos mixing philosophy, what immersive projects they’re currently working on, as well as where they think the industry is headed.

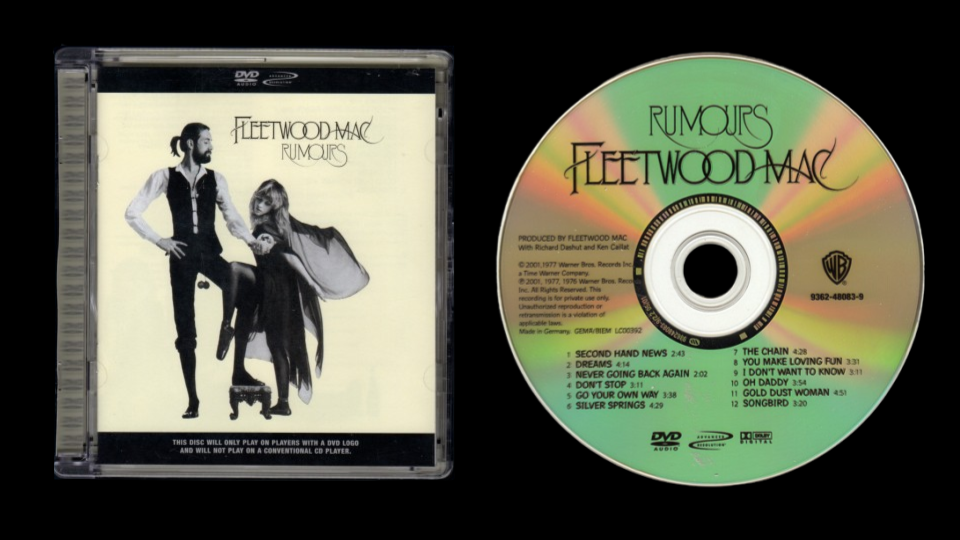

When 5.1 surround music was introduced in the early-2000s, you were among the format’s earliest adopters. Tell us about remixing Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours in 5.1 for the DVD-Audio format. Did the band have any input into the mix?

Ken: Yeah, I was already set up for 5.1 at the time and I wanted our first big project to be the Rumours album. I called Warner and they were completely on board with the idea. The band came over and sat in as we were working on it.

I remember Lindsay [Buckingham] would say “where’s the beef on this song?”, meaning the bottom-end [laughs].

That’s interesting, because more often than not–both with 5.1 back then and Dolby Atmos now–it seems like the artists aren’t always involved in the remixing process.

Claus: Joni Mitchell did come in and listen back to the five albums of hers we recently mixed in Atmos. It’s not like she sat in with us every day, but she did have some input. She really knew her stuff and she did make a couple minor adjustments to suit her original intentions.

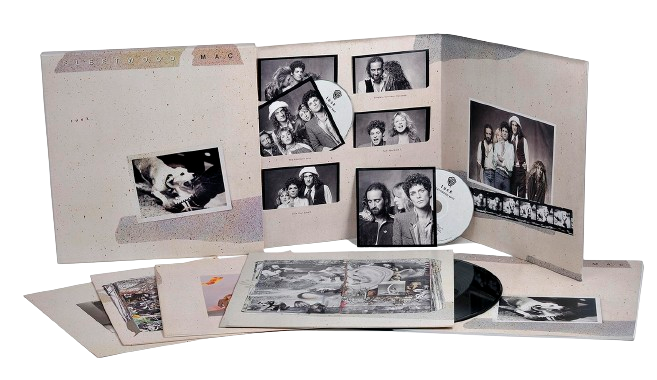

Going back to the four Fleetwood Mac albums you remixed in 5.1 (1975’s self-titled album, 1977’s Rumours, 1979’s Tusk, and 1982’s Mirage), I’ve always found it interesting how these mixes frequently bring out buried and/or unused instrumentation to the fore–such as the snare drum and steel guitar accompaniment in “Never Going Back Again.” Were you intentionally going for a different sound than the original versions?

Claus: We did those when I was Chief Engineer at 5.1 Entertainment Group. I’ve been working on-and-off with Ken for 25 years now, and he has never been one to lean against the original stereo. Even with Joni Mitchell’s music in Atmos, we tried to take it as far as we felt we could without bringing extra parts or changing things too much.

Ken: When I did the original “Never Going Back Again,” we had the picking guitars, vocals, and everything else you hear in the original–but we were also experimenting with marching snares, triplet snares, and other things. For the stereo mix, the band decided to keep things simple. When we did the 5.1, all the extra space allowed us to use that other material we’d originally recorded. That’s my thinking: if we had something that didn’t work in stereo–but does fit in 5.1 or Atmos–I’ll put it in.

If possible, explain your approach or philosophy to mixing music in surround sound. Some mixers seem to prefer a more conservative route and use the additional speakers primarily for reverberation, while others are more experimental and place isolated instruments behind or above the listener. Are you trying to create a ‘center of the band’ or ‘in the audience’ perspective? Where do you draw the line between ‘immersive’ and ‘gimmicky’?

Ken: You know, every song has its own heartbeat. So I start by pulling all the faders down and trying to figure out what the core of the music is. Then I’ll add in all the other instruments around that.

Claus: With Joni, some songs on For The Roses (1972) were just vocals and piano. Those obviously get treated very differently than something like “People’s Parties” from Court & Spark (1974), where you have repeating voices and all kinds of other stuff going on. The technology allows us to put anything anywhere, so it really comes down to kind of getting an impression of what the individual song calls for–if that makes sense.

Ken: If we're allowed to wander off and do our own thing, then we’ll try to do that. But sometimes the mandate is to match the stereo, because the Atmos mix is the default choice on the streaming services. So if it doesn’t fold right or doesn’t sound like the original, people get upset.

Out of the four ‘70s Joni albums out in Atmos, my favorite was definitely The Hissing Of Summer Lawns (1975). There are so many interesting sounds on that record, especially on a song like “Harry’s House/Centerpiece” where there’s the heavy jazz influence and even some almost-psychedelic passages with voices moving all around the room.

Claus: It’s always a balancing act, because you want to show off the 3D environment–especially for people who have a multichannel speaker system. Once it falls to binaural, you have to make sure that all the movement and other effects don’t get overwhelming in headphones.

We always advise that there’s nothing wrong with starting on headphones, but you have to check your mix in the speaker environment so it works in both places. We work on speakers first and check headphones last, because we feel that the true home of an Atmos or spatial mix is a multi-speaker system. The binaural will get better over time, but it’s an algorithm. It’s just math rather than true binaural recording, which can sound amazing.

You’re referring to recordings done with a binaural mic, like the Neumann KU100?

Claus: Yes. It’s a dummy head: two microphones with earlobes, right? It gives you the physics of a human head and torso blocking or reflecting some of the sound. You can actually get the genuine forward, back, up, and down directional information from headphones with a true binaural recording.

What Dolby calls binaural is a great approximation, but it's not as good as a true binaural. The great thing about object-based mixing is that as binaural emulation improves over time, we won’t have to go back and create new masters.

I always thought it would be an interesting experiment to take a binaural mic like the KU100 and record in a 5.1 or Atmos music mix from the sweet spot in a proper multi-speaker environment. I imagine it would compare favorably to the binaural algorithm?

Ken: The issue with true binaural recordings is that they don’t translate to speakers. They have kind of an old ‘tinny’ quality, and EQing that out to make it work on speakers will eliminate the locational information.

Claus: A dedicated binaural mix would have to be locked to headphones. This is where Dolby Atmos excels: it knows what your playback device is and automatically defaults to binaural, stereo, or multiple speakers.

It’s a little bit scary for an engineer to sit back and give that kind of authority over to the playback device, right? When we did stereo or even 5.1, it was linear mixing rather than object-based mixing–so we had complete control over what went to each individual speaker. We don’t have that degree of control with object-based mixing, but the technology is so much more flexible.

If you were to make a dedicated binaural recording, it’d be hard to prevent people from listening to it on speakers and then getting confused about why it doesn’t sound good.

Linear translation is one of the reasons why 5.1 music could never really catch on beyond an enthusiast audience, because the only way to properly listen back is on a home theater system with five speakers placed in the same approximate locations as the mixer’s studio. Personally I would always choose to listen over speakers, but–in order for Atmos or spatial audio to become an industry standard–I accept that it has to translate to headphones and other playback environments.

Claus: I completely agree. DVD-Audio and Super Audio CD were great formats. Ken and I fell in love with the spatial audio at the time, but we couldn’t justify doing these mixes just for the niche audience that could afford a surround speaker system at home. It‘s called the music business for a reason, and there just wasn’t enough money in it for the labels to continue commissioning 5.1 mixes.

The next remixing effort was for the Rock Band and Guitar Hero video games. We went back and made stereo stems for instrumental mixes, so you could have the bass and guitar stuff separate for those games. Unfortunately, stems tend to get used a lot of the time today to make Atmos mixes. Ken and I are huge advocates of going back to the original Pro-Tools session or the original tape, depending on the age of the song, so we don’t get locked into using a certain reverb or compression setting.

Ken: One of the other problems with 5.1 is that you had to sit in a specific location. I remember when we first did some 5.1 mixes, I played them back for my daughter Colbie Caillat. I was trying to get her to move to the center and she said “Dad, why do I have to sit still in one place?" So that’s where headphones come in really well.

You mentioned how stems are often used to make Atmos mixes rather than a true dry multitrack, which I agree can really limit the scope of the immersive experience. For Joni Mitchell’s albums, I assume you had access to the original tape transfers?

Ken: Yes, and it was all beautifully recorded.

One thing that’s so interesting to me about 1970s-era analog recordings is that engineers would often make mix-related decisions during the recording process, like tracking with EQ and compression on the way in. When you first received the multitracks for those Joni Mitchell albums and started pushing up faders, did you find that the ‘sound’ and character of the original mixes was already baked in to some degree–or was there still a lot of work to be done in terms of matching effects and emulating the overall feel?

Claus: I’ve never had multitracks where I could just do faders up, because there are additional considerations besides sonics. You always have to deal with other factors like dynamics, compression, and placement.

That’s another reason not to use stems, because we have so much more dynamic bandwidth in Atmos. Stereo had been going through the loudness wars for years, where you can’t hear any volume difference between a verse and a chorus. By going back to the original multitrack, we’re able to retain the intended dynamics.

Ken: We also have much better effects now than they had back then, especially the reverbs. With Joni’s Miles Of Aisles in Atmos, it really feels like you’re in the amphitheater on a hot summer’s night.

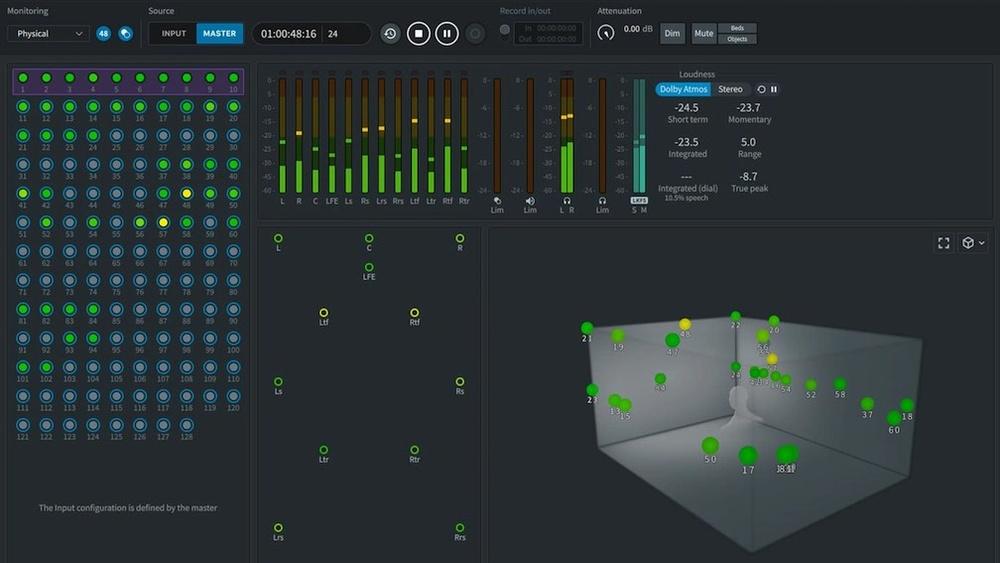

Claus: We’re currently seated in the control room of our facility, which is a 9.1.6 environment, but we’ve also built a live room behind us. It’s not like a football field-size room, but it's a great overdub space with a piano and a good mic selection. I know we’ve been talking about Joni’s albums from the ‘70s, but the idea is also to have new artists experience the artistic process in a spatial environment from day one–rather than it being done after-the-fact.

Going back to what we were saying about always using the original masters, I’ll take an analog multitrack from 1973 anyday over a Pro-Tools session from ten years ago. Getting those creatures back to life is almost impossible, especially if they had sent audio through outboard gear like an analog compressor and didn’t print their work. So there can be a fair amount of forensics there. I’ll start working in stereo and try to at least get in the right sonic ballpark, then begin spreading things out.

The goal isn’t just to copy, but also to enhance. We want to make sure that you recognize the song and don’t feel cheated by a new version, but also see that you get extra for your money–if that makes sense,

Ken: I always want it to be a really amazing, moving listening experience for the listeners. We put 110% of our effort into perfecting all those little details, and I think you can really hear it in our work.

Claus: We’ve also worked with some newer indie artists that are not restrained by history. It’s fun to talk with a young artist and see how experimental they feel.

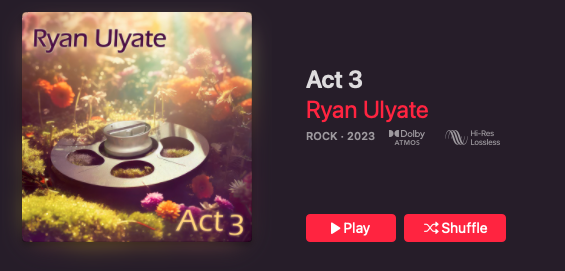

Joni Mitchell’s music is not meant to be a rollercoaster, at least in my opinion. But there are certain songs from other artists that work with a more extreme treatment, like Ryan Ulyate’s Act 3 album. He was very aggressive in his artistic vision and presentation of his music, which is a great testimony to how the technology can be used, but may not be appropriate for the legacy albums. So there’s also that balance of what’s appropriate for the artist and song.

Ken: With the For The Roses album, we actually had to use some de-mixing software to get more separation out of it. As you probably know, everyone’s starting to use AI for de-mixing.

Claus: Yeah, there was a song that was basically just her on a piano. When you start to separate the stereo piano recording from the vocal mic in Atmos, there’s a tremendous amount of bleed. We were able to go in and remove a lot of the vocal bleed from the piano, so we could separate them more in the mix.

Sometimes it’s the simplest songs that take the longest. There was a fair amount of stuff like that with the Joni albums, but we never went overboard and replaced anything. We made sure we used the tools appropriately.

I’m guessing that in 1972, For The Roses was probably recorded on an 8-track machine?

Claus: Yes, but there were some songs where they’d only use five or six tracks.

So how do you go about mixing six tracks into an 11 or 15-speaker environment?

Claus: It’s all objects, right? You position them anywhere in the listening space, so the signal fills out multiple speakers.

Ken: Even if it’s just one instrument like a piano, we can make it sound really big and present. You can literally feel the hammers moving in the room.

Even without visual confirmation from the Dolby Renderer display, I can tell from listening that you really took advantage of the object-based mixing process. There are some elements that are clearly tied to the floor or ceiling arrays, while others are hovering somewhere in-between. It’s especially noticeable with Joni’s vocals on some songs, like “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire” from For The Roses: you can hear her voice in the front speakers, side speakers, and front height speakers.

Ken: Yeah, the top speakers are great. I liked to put Joni’s voice a bit closer to the listener and slightly elevated, as if she was standing up and performing right in front of us. Having all those speakers working in tandem really helped give an almost-live quality to her voice.

It’s funny, because I remember being perfectly satisfied with 5.1 and wondering how much more immersive the experience could be. One of the first songs I listened to in Atmos, on a crude 5.1.2 setup, was The Doors’ “Riders On The Storm.” Of course they put all the thunderstorm effects in the top speakers, which was enough to completely sell me on the new format.

Claus: One of the first songs mixed in Atmos, basically as a demo, was Elton John’s “Rocket Man.” I don’t think they did a full object-based mix of that–it’s more like an enhancement of the original 5.1, with some vocals flying over and around you–but it shows off the format well.

Earlier, you had spoken a bit about starting your Atmos mixes in a speaker environment and then finishing them on headphones. Do you find you have to make a lot of alterations to the speaker experience in order to make it properly translate to binaural? Is there a lot of switching back-and-forth between the two formats?

Claus: Not a lot of going back-and-forth, but I think that’s mainly because we’re mixing in a calibrated room. Room set-ups are a whole separate discussion, and we worked very closely with Dolby to configure this room.

I find there are very few compromises with binaural, but a lot of the time it has to do with use of the LFE channel. I’ve never really understood being aggressive with the LFE, because the left and right fronts channels are still full-range. So you kind of make the assumption that there is some type of bass management happening on playback.

Center speaker usage can be very deceptive. On headphones, you cannot hear any difference between center speaker only or phantom left and right. In a room, you can definitely tell the difference and we usually try to do a blend.

If you move an object in the center forward position, the sound comes from the center speaker only. Let’s say you’re using a stereo reverb on the same element: where do you think it comes back? The front left and right speakers. So you end up with a singer that’s totally naked in the center, and very few artists enjoy that.

It’s also worth noting that the center speaker isn’t always matched to the front left and right on a consumer system, because it has to fit under the TV. I’ve heard some Atmos and 5.1 mixes where all the bass is isolated in the center channel, which to me seems like a dangerous proposition given that it’s most likely the smallest speaker in the whole array.

Claus: It also helps to understand the difference between a bus and an object. With a bus, you can create a phantom image whereas with an object you can’t. So if you were to make the bass an object and put it center front, there’s no way to distribute it out unless separate sends out to the left and right. If you send it through a bus, you can control the percentage between phantom and real center.

I’ve noticed that in Pro-Tools, the ‘divergence’ control that allows you to control the spread between adjacent speakers doesn’t work with objects.

Claus: Yes. In Pro-Tools, the only control you have with objects is size. That’ll incorporate other speakers, including the ones behind you. So if you want something just to come from the front left and right, the only way to do it is with a bus.

I’ll usually set a phantom image with a bit of support in the center. so the vocal still feels anchored to the middle if you’re sitting off to one side.

To your earlier point about the LFE channel, another potential pitfall is that the LFE signal doesn’t get filtered when you bounce your mix. So you’d be relying on the listener’s crossover frequency setting to ensure there isn’t excessive low-end response.

Claus: Yeah, but you can catch that in the render process. I always make sure I filter the LFE before submitting a mix. You can’t rely too heavily on technology. [laughs]

When you’re finished with an Atmos mix, is there an additional mastering step? Another interesting aspect of working in Atmos, at least as I understand it, is that there’s no master bus that all the objects pass through.

Claus: Pro-Tools now has 9.1.6 bussing, and you can take an ADM to a mastering house. We’ve worked with a few mastering houses, and we’re certainly fans of QC. It’s always good to have a second set of eyes and ears. We would love to invite other engineers to come listen to their mixes in our space, even if they’ve done 90% of the work on headphones. Our goal is to raise the overall quality standards of the technology.

In the case of the Joni mixes, those went straight from us to the label. It’s my understanding that the project did not go through a mastering process, but that doesn’t mean it’s not needed.

Ken: Like Claus was saying, I’d love to offer the labels a QC testing service. We have a really nice system here, so it’d be great to get people in to listen back to their work in a really good environment.

Claus: We work in a control room with a somewhat small sweet post, but we also built a 12-seat theater with a 14-foot screen. The idea there is to have people come in and listen back to the album. We strongly believe that it’s only a matter of time before music videos with Atmos become a big thing, so we’re adjusting our workflow for that.

Not everybody has a calibrated room and a calibrated theater like we do, so we definitely want to help out both labels and engineers alike. Even just something as simple as saying “you might want to be careful about how you’re using the center speaker in this part of the song” or “it doesn't necessarily have to be that compressed.”

I mean, we have a lot of friends in the industry and we all listen to each other’s work. In fact, we just went to Ryan [Ulyate]’s playback party at the Dolby Theater the other day.

Ken: I wish Dolby would put out a list of approved hardware. We had a wealthy client come in recently that wanted to build a system, and I wasn’t sure what gear to recommend.

Claus: Nakamichi recently came out with a really amazing soundbar system. It’s got real speakers and a double sub. Do you remember the high-end ‘dragon’ cassette recorders they used to make?

I’ve heard a lot of buzz lately about the Sonos ERA-300, though I haven’t listened back to one myself. The ability to use two of them in tandem with the ‘Arc’ soundbar for a full 7.1.4 experience sounds really intriguing. In any case, it would be great to see an inexpensive, easy-to-set-up wireless system become available. Building a traditional home theater with more than seven wired speakers and a receiver is very much still enthusiast territory.

Claus: Dolby is working on something like that now, in tandem with their new TV service. We heard a demo at Avid recently.

Another great thing about Atmos is that even if you have a 5.1 system, putting up just two more speakers as heights really enhances the experience. With the amount of receivers and soundbars that are available nowadays, I really think there are some decent options.

Even just picking up an Apple TV and listening back to Atmos music in 5.1 is a great place to start. The Joni mixes seem to translate well to a traditional six-speaker environment.

Claus: I always go through all the speaker configurations in the Dolby Renderer towards the end of the process. I’ll start with “physical” (9.1.6 for us), then work my way all the way down to 2.0 just to make sure nothing is blaring out of place.

I understand that the Asylum Albums Atmos mixes were done as part of the ongoing Joni Mitchell archives project. There were physical releases of the albums on CD and vinyl, but the Atmos mixes remain exclusive to the streaming services. Do you know if Warner/Rhino plan to issue the Atmos mixes on Blu-Ray?

Claus: Yes. Back when we first did the mixes, our A&R rep at Rhino was talking about doing a Blu-Ray release with all the uncompressed audio. I’m surprised it hasn’t come out yet. Maybe early next year?

That’s great news! It would be cool if they included the original quadraphonic mixes of Court and Hissing as well. Have you heard the quad versions of those albums?

Claus: Yeah, we've got the original quads. We asked the label for them, just to get a feel for how aggressive they were back in the day.

Ken: Back when I was doing Rumours, one of the studios we were working in had quad monitors. I remember playing around with it, putting the drums in the front and guitars in the back or some other combination. There weren’t really a lot of choices because it was an even amount of speakers. You needed to have something in the center.

Claus: I was born in ‘72, so I kind of missed the whole quad thing–but it sounds like there was a similar issue to 5.1 with linear translation, so the listener could only consume it in one way. As much as we want people to listen in a full-speaker environment, I think that compatibility with headphones and soundbars that are Atmos-capable really gives us a good shot at selling the next format. We’ve gotten to a place where listeners can really enjoy the spatial format without having to invest in a full-blown system.

Ken: If someone’s invested in an Atmos or surround system, I think it’s kind of our obligation to treat every project like it’s a demonstration of the Atmos technology. We want to impress each listener as much as possible and really turn them on to how great the format is.

Claus: You had asked earlier if we had to do any tricks with the multis on Joni’s stuff and we didn’t, but Ken has done that a couple of times on his multitracks. Sometimes he’d re-amp guitars during the mix process, so you have to go back and start matching that stuff. It’s kind of fun because with the Fleetwood Mac stuff, we’ve made Lindsay’s tone a bit more aggressive. He might seem a bit brighter and more upfront than in the original stereos.

One more question: if given the opportunity to mix any previous album in Atmos, what would you choose?

Claus: My first thought was something like Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1979). I’d heard they’re working on it and my fear is that they’re going to overdo it. I’m always a bit nervous when classic albums of that stature get mixed into this format.

Ken: Maybe the Moody Blues?

Aside from Joni’s Asylum Albums, are there any other Atmos mixes you’ve done that are currently available to stream?

Ken: We did Colbie Calliat’s Coco (2007) and Along The Way (2023). Also the Gin Blossoms’ New Miserable Experience (1992).

Claus: There’s a Lady Antebellum album too, and also some indie artists.

So you guys weren’t involved in the recent Fleetwood Mac releases? Everything from the 1975 self-titled “white album” through Tango In The Night (1987) is currently streaming in Atmos.

Ken: No. Lindsay had hired an engineer named Chris James to do those.

Claus: All the Fleetwood Mac 5.1’s that were released on disc are ours, but not the new Atmos versions.

Joni Mitchell's The Asylum Albums (1972-1975) is a nominee for IAA's 2024 Listener's Choice Award!