Richard Chycki is a multi-platinum mixer and engineer whose clients include such rock royalty as Rush, Aerosmith, Dream Theater, Skillet, Mick Jagger, Alice Cooper, Pink and many more.

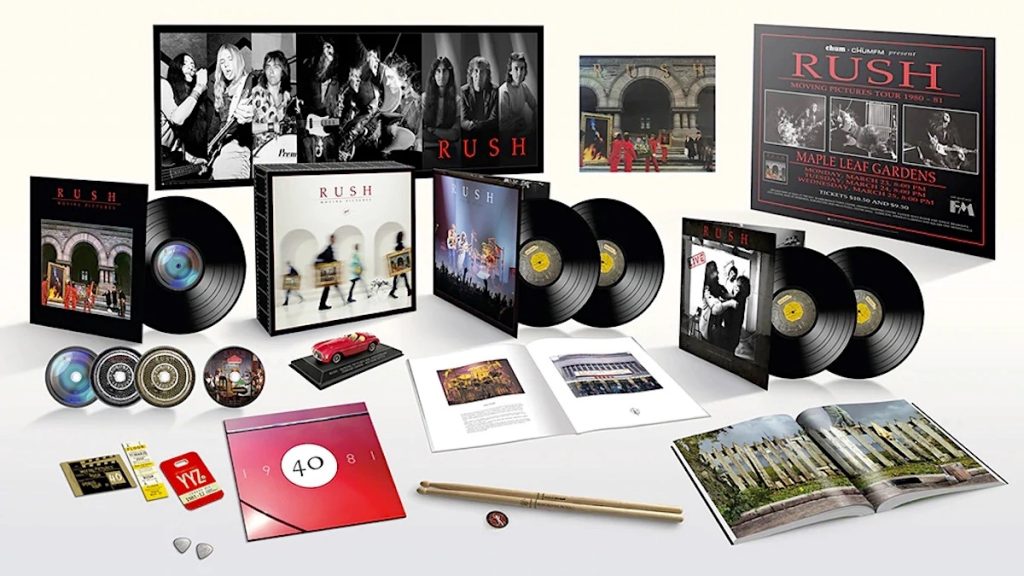

Known for his pioneering mix work in multichannel audio, prog icons Rush entrusted Chycki to remix the multi-million selling 2112 (1976), their career pinnacle Moving Pictures (1981), as well as A Farewell To Kings (1977), Hemispheres (1978), Signals (1982), Snakes & Arrows (2007) and Fly By Night (1975) in 5.1 surround sound. More recently, he’s mixed Moving Pictures and The Tragically Hip’s Road Apples (1991) for their respective 40th and 30th anniversaries.

How did you first get into engineering and producing music? What do you enjoy about it most?

I got into recording music because I thought that as musicians, that’s what we were supposed to do: write a song, then perform and capture it. It was a naive way of thinking, but it turned out well in the end.

I practiced a lot, then read and experimented even more in a studio that I could use while I oversaw a rehearsal facility. Like most people, I was trying to get my band signed and tapes ended up on record exec’s desks. I got calls about who recorded my demos and labels started to hand me artists to track songwriting demos, which quickly moved to albums. From that point on, it was a matter of networking.

I really enjoy the intersectionality of technology and creativity when it comes to recording and production. I also get to perform and write songs on occasion, so it makes for a good multi-faceted outlet.

When were you first introduced to the idea of mixing music in surround sound?

While I was working with Aerosmith in 2000, an industry friend of mine was chatting about the success of adapting theater format audio to an audiophile immersive music format, as well as the many new possibilities for re-imagining then-current mix approaches. Having enjoyed discrete quadraphonic reel-to-reels of Pink Floyd and The Who, the concept was very attractive to me as I had always felt that quad was so far ahead of its time.

You’re well-known in the immersive music community for your 5.1 remixes of Rush’s classic albums from the ‘70s and ‘80s. How did you come to be involved with the band?

I was asked to engineer/mix Rush performing “Closer To The Heart” live-in-the-studio as part of a charity event for the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Alex [Lifeson] and I spent so much time hanging out and laughing. There was great chemistry. He called me a few months later asking if I’d be interested in mixing the R30 DVD. Again, we had a lot of fun working together and the project was well-received. 18 years later, here we are.

We’d love for you to elaborate a bit on how you approach surround sound mixing. Can you talk about your decision-making process for utilizing the extra channels? Are you trying to create a ‘center of the band’ or ‘in the audience’ perspective? Where do you draw the line between ‘immersive’ and ‘gimmicky’?

These are great questions. Approach is completely based on content tempered with the project’s intent. Is it a live show? An upmix of a vintage project or a post-release current one? Or is it a new release where we are creating the production from scratch?

For live, I usually go for an audience perspective with a few possible features like flying things during drum solos/vignettes or an increase in echoes and ambience during solos, for example.

For live albums that I’ve recorded, I have a matrix of 8-10 mics positioned from front to rear of the venue including a Blumlein pair over the sound man, which I balance to re-create the immersive soundstage. When I don’t have that multi-mic option, I re-create the immersive ambience with digital reverbs.

Upmixing a vintage project involves recreating the mix first in stereo, constantly referring to the original stereo master, and then spreading the mix out into immersive. Modern releases have often been submixed to stems, so I’ll work with those in Atmos.

In the studio, positioning possibilities vary wildly depending on track density and production value desired. Anything from a static ‘In the room’ approach to complete swirling motion is possible. That’s what makes immersive so exciting, the endless possibilities.

Though Rush’s music can be quite complex, there aren’t actually all that many layers to their studio recordings - many of their songs have a simple “power trio” arrangement of just drums, bass, vocals, and double-tracked electric guitar. Does the limited amount of individual elements in play present challenges for expanding the music into a surround format?

The masters for Moving Pictures are spread across two 24-track analog machines. The album is certainly not sparse when compared to Fly By Night (1975) or the self-titled white album (1974).

Even with a more bare three-piece section – like the guitar solo portion of “Tom Sawyer,” for instance – the kit was recorded with enough discrete channels to get the lift and spread required to make Neil [Peart]’s kit sound as wide and massive as his playing. The guitar slap and chorus effects that Alex was using can offer the same added dimensionality. A section like this is static mix-wise, so the mix doesn’t interfere with the musicians’ contributions when compared to the constant motion of many elements in a track like “Vital Signs.” Again, it all depends on the source material and assessing the mix direction to best support the artist.

There tends to be a lot of online debate over remixing classic albums, as some hardcore fans feel there’s an element of “revisionist history” to the concept. However, one could also argue that an entirely new mix - especially in a multichannel format like 5.1 - is intrinsically a new take on the material. In order to please these fans, did you feel an obligation to closely replicate the instrument balances and effects used on the original mixes?

Bands for whom I’ve remixed in immersive definitely want the initial mix maintained, but also want to make use of the additional space afforded by the format. There is little latitude to remix the original album, as the term ‘remix’ would be used to refer to a re-imagination of a mix to modern or radically different standards from the original. In fact, a fair bit of work goes into the recreation of vintage effects, eq’s, etc with modern tools.

The only time I’ve worked with an original asset and been asked by the artist to completely re-mix it was for several tracks of Rush’s Vapor Trails (2002) that I did for the Retrospective 3 compilation in 2009.

I think that a lot of fans don’t realize how much work happens behind-the-scenes with these immersive remix projects. I imagine there’s a lot of detective work involved in trying to piece these albums back together from session tapes, locate all the correct takes, etc. Did you face any such challenges with the Rush 5.1 remixes?

Yes. I refer to the original track sheets and mix recalls, if they are available. I’ll also insert a print of the original mix that runs concurrently with the multichannel, so I can constantly refer back to the original for comparison.

Unlike some of the even older Rush albums I’ve mixed, Moving Pictures didn’t have multiple drum takes or partially completed takes to sort through. The masters I received were two sets of digitized unresolved 24 track masters. The first order was to assemble the masters into a single session. While some comps are obvious, others involve going through tracks one at a time. Alex’s rhythm work is so consistent that a lot of original bed takes were intact, and they sounded great. The question came down to whether they were used in whole or in part.

Tell us about mixing The Tragically Hip’s Road Apples (1991) in surround sound. As with Rush, this seems like a relatively-sparse recording that’d be difficult to translate to an immersive soundstage.

Rush, being a progressive band, allows more latitude for motion and angularity as needed to contribute to the mix atmosphere without coming across as gimmicky. An artist like The Tragically Hip is very earthy and organic, so a more stripped back immersive environmental approach was definitely the way to go. Imagine leaning against the pool table in the room where the band was performing and watching them perform a track: that was the mix approach.

I was very fortunate that [original engineers] Bruce Barris and Don Smith captured the ambience of various parts of the mansion in which they recorded the album, offering me a great template to re-create a multichannel version of it. Effects and placements are definitely three-dimensional, but the amount of mix motion is limited as that would quickly come across as gimmicky in this particular situation.

You’ve recently become an advocate for the new Dolby Atmos immersive format, having created new Atmos remixes of The Tragically Hip’s Road Apples (1991) and Rush’s Moving Pictures (1981). How does mixing in Atmos differ from 5.1? What kind of elements do you typically place in the height speakers?

A 5.1 mix involves literal placement of elements within the sound field of a single plane of speakers in a narrowly-defined configuration. If the speaker configuration changes to 7.1 or 9.1 for example, those additional speakers are not used unless DSP gets involved to ‘fake place’ audio in those speakers. Conversely, going from 9.1/7.1 to 5.1 involves some sort of downmixing or the audio assigned to those speakers is lost.

Atmos uses a combination of a 7.1.2 bed plus a series of objects that use metadata encoded into the mix container to actively adapt to the number of speakers in a setup. As a result, the format is inherently more resilient to varying listeners’ playback systems and a mixer’s intentions are less susceptible to compromise.

With regards to placement, ambiences, both echoes and reverbs, in all speakers (minus sub) are first order and any source that benefits from a lift – drum cymbals, vocal, solos, pads. Using Rush’s “Witch Hunt” as an example, most of the intro has all elements assigned as objects so they can be placed and panned in any direction through any speaker. There is a finite number of objects available, so it’s important to look ahead and determine which element will be assigned as an object or become part of the bed track.

Can you talk about any current immersive projects you’re working on?

I have several immersive projects underway right now, but I can’t discuss them until the band or label issue press releases. However, I can say that immersive is alive and continuing to grow.