Nathaniel Reichman is a Grammy-nominated mixer, engineer, and music producer who has worked extensively in television, film, and classical music. His work can be heard on numerous hit children's television shows including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, WordWorld, Bubble Guppies, and Wallykazam!

In the world of film, he has contributed to Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant, Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi, Abel Ferrara's 4:44 Last Day on Earth, and the Showtime documentary Comedy Warriors. In the realm of music, he has worked on major contemporary classical albums from well-known composers such as John Luther Adams and Philip Glass.

He’s also an innovator in the realm of immersive audio, having created 5.1 surround sound and Dolby Atmos mixes of John Luther Adams’ acclaimed 2018 work Become Desert. We had the chance to chat with Nathaniel about his early career, experience working with surround sound, and where he thinks the industry is headed.

How did you first get into engineering and producing music? What do you enjoy about it most?

I went to Bennington College, where the electronic music pioneer and historian Joel Chadabe was teaching. Joel saw electronic music as being a part of the whole of contemporary art. He drew analogies between the paintings of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman when teaching composition classes. His perspective gave me a deeper understanding of what some of the great 20th-century composers were trying to achieve. Karlheinz Stockhausen, Alvin Lucier and Denis Smalley weren’t just technicians, they were artists pushing the envelope with a new set of paint brushes.

I wanted to write electronic music too, and spent a lot of time in college learning the studio tools of that era. This naturally led to recording and producing other people’s projects. Upon graduating, I was somewhat surprised to discover that all of the technical skills that I’d developed in the pursuit of modern music lent themselves really well to music for advertising and television. It’s hard to say what I enjoy most, but every day I wake up eager to get to the studio and I feel very fortunate that this is my career.

Are most of your mixing projects done in conjunction with video (live concerts, film, etc) or are they audio-only?

In the early days of these immersive formats, maybe five or six years ago, I was pretty convinced that our television and film clients at Dubway Studios would be the first to request a mix in Dolby Atmos or Auro-3D. It was quite a surprise to me when our music clients took the lead and began asking for immersive mixes.

In 2022 we’re at an unusual juncture, where most television and indie film work is 5.1 with only some Atmos requests. On the other hand, the music clients have spec sheets that run the gamut, often demanding vinyl LP, stereo CD, stereo high-resolution and 5.1 mastering, as well as Dolby Atmos mixing and mastering.

How is the process of mixing audio for film different from mixing music?

I can’t overstate how important the dialog pre-dub is in a mix for film or TV. I’ve mixed television shows in which I spent 70% of my time with the dialog. After that superstructure is in place, you can almost hang the sound design and music on it. That equivalent aural framework really doesn’t exist in music. Each piece of music has its own demands.

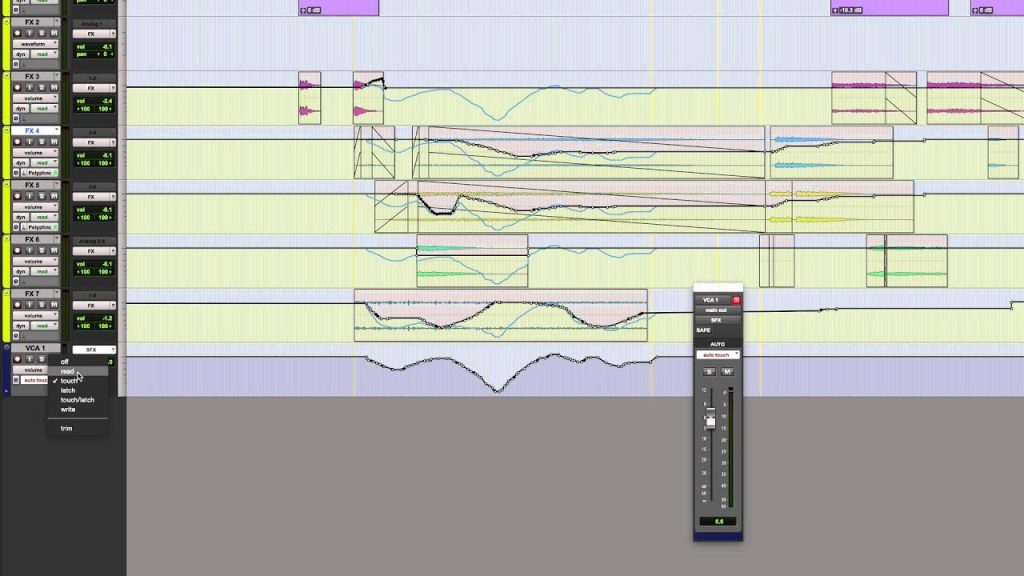

There’s an album I mixed that’s coming out in September. On this album, the percussion and the brass were remarkably well-recorded by Bill Maylone. From a purely aesthetic level (instead of a compositional level), I put the percussion up in the proper panning, almost without any EQ or compression, and hung the rest of the orchestra around that. The dynamics were extraordinary. I think if you look at the mix session, you’ll see a straight line where the percussion VCA stays ruler flat, and then a zillion squiggly lines as the strings, winds and choir work their way around the percussion.

Do you have any anecdotes from your time working as music producer/editor on The Revenant?

I’m proud of my short stint on The Revenant. Alejandro Iñárritu really understood John Luther Adams’ music. It was an incredibly busy time for both of them, so John asked me to comb through his catalog and find the best options for the opening scenes of the film.

The score was in flux for some time, but in the end I was quite pleased to hear my mix of Become Ocean alongside great original cues from Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto. For the Atmos fans reading, I remixed Ocean in Atmos for the release of the Become Trilogy remaster. That’s the mix to listen to. It’s better than the original.

When were you first introduced to the idea of mixing music and/or film in Dolby Atmos?

I followed the technical discussion of Dolby Atmos from the very beginning. In its early days (Disney’s 2012 release, Brave, was the first movie mixed in the format), it seemed out of reach to everyone but a few top-flight L.A. film mixers working on the biggest stages in the world.

It was early 2017 when a colleague of mine, John Bowen, had been exploring immersive audio technology from the standpoint of a binaural headphone experience. He convinced me to demo an early version of the Dolby Atmos Production Suite. Initially it seemed like a clunky QC tool, so I wasn’t terribly enthusiastic about it.

Bowen used the objects in the Production Suite to flesh out a quirky little sound design sequence and sent me a binaural WAV file. I almost fell out of my seat when I heard it. I spent the next day A/B’ing conventional panners and the Dolby binaural panner. I then texted Bowen,

“Once you hear a binaural panner, you can’t unhear it. Why would we ever use a conventional panner again?” He texted back: “Good question. Don’t know.”

Having previously worked in 5.1, do you feel Atmos is an improvement?

I’ve done a lot of work in 5.1, both for albums and television shows. One gets very excited about 5.1 because the center channel gives everything a tangible, dimensional quality, and the surrounds promise a sense of space. I often felt letdown by the format too, because most 5.1 installations left these big empty gaps on the sides and often sounded thin in the rears.

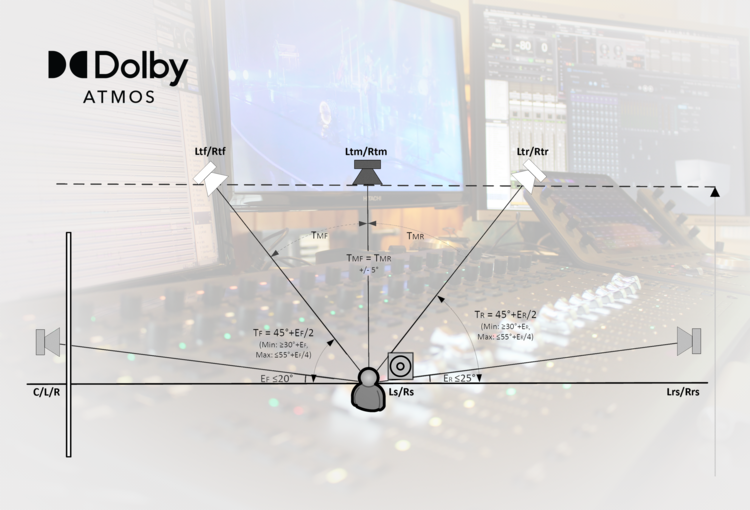

The film people are smart and addressed both of those problems with the 7.1 format, but 7.1 is obscure when you look at the installed listener-base in any other context except movie theaters. Dolby’s uncompromising effort in the development of Atmos was a huge breath of fresh air. It offered complete three-dimensional panning around the room, equally distributed bass-management, and the adoption of the “object” concept.

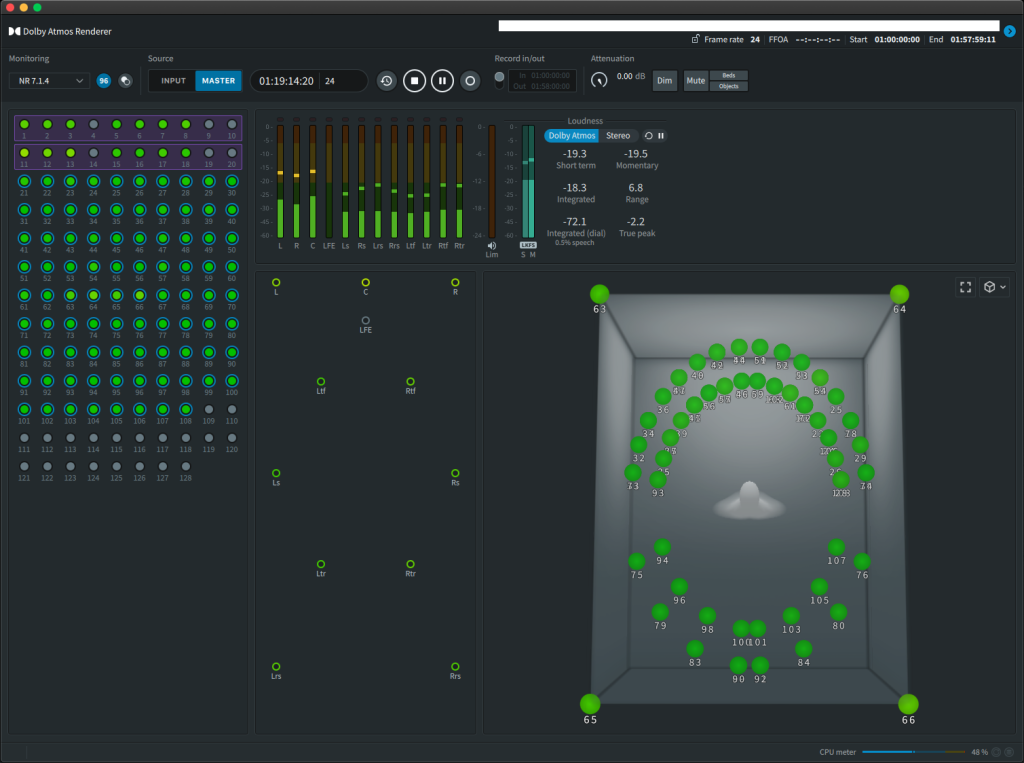

For people in the industry who aren’t engineers, it’s hard to explain succinctly why object-based panning had to be invented. I’ve found it much easier to simply demonstrate aurally the difference between objects and beds when I’m hosting composers or conductors in the mixing studio. We could talk about it endlessly in this interview, but five minutes of listening is worth five thousand words.

How do you decide which elements are assigned to the “bed” portion of the mix versus the “objects”?

I thought that question might be coming! I’ll do my best to use less than five thousand words. [laughs] In a well-tuned Atmos room, if you pan a mono track (recorded speech is very good for this) around the room and maybe up to the ceiling, and you do that panning as a bed, there’s sort of a vagueness about the location in space. You might think that adding more speakers would solve this vague quality and help you identify where that person is talking in three-dimensional space, but it turns out that it doesn’t really help that much.

When you take that same track and switch it from bed mode to object mode, the perceived location accuracy goes from “sort of over there by the window” to “Oh-my-goodness, that person is talking exactly three feet to my right and 40 inches from the ceiling!” In other words, the perceived location accuracy improves by a significant factor. That’s exciting, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that everything should be objects.

Objects really work well with individually-recorded sounds in a pop music mix, or with sound effects that are designed to capture someone’s attention. However, if you’re working with something like a spaced pair of microphones recording a string quartet or symphony orchestra, the binaural information that objects give you is redundant because that spaced pair is naturally delivering binaural cues to the listener. So for the spaced pair in a concert hall, those mics really sound best as beds.

Then, as you scale up to the immersive 7.0.4 microphone arrays that people like Morten Lindberg have made popular, I’ve found that those arrays sound the most natural as beds. It’s typically the spot microphones that sound best as objects.

With the introduction of Apple’s “Spatial Audio” format, it seems most listeners are experiencing a binaural approximation of Atmos over headphones rather than the full immersive experience on a home theater setup. Do you ever check how your Atmos mixes sound on headphones, or are they only meant to be heard on speakers?

I check on headphones all the time. In fact, I have my mixing room set up in such a way that I can switch between 7.1.4 loudspeakers, stereo, Dolby binaural, and Apple Spatial Audio at the press of a button. The trick is to strike a balance between the loudspeaker approach and the headphone translation.

When I was mixing John Luther Adams’ Arctic Dreams, I had the singers lined up against the left and right walls, and it was absolutely beautiful on loudspeakers. However, those lines folded-down into the binaural headphone mix and the singers stacked up on top of each other in the corners with no real perceivable space around them. So I found a way to stage the singers in arcs. Those arcs were still beautiful on loudspeakers, and worked really well in binaural. It was a good balance.

That said, some of my favorite Atmos mixes from other engineers are really adventurous, and I worry about the industry as a whole mixing too conservatively in the format.

Can you talk about any current immersive projects you’re working on?

I finished the mix for Sila: The Breath of the World just a few days ago, which is an hour-long orchestral and choral piece performed by The Crossing, The JACK Quartet and the University of Michigan Orchestra. We had the resources to record it in early 2021, before everyone was vaccinated, so we took sixteen musicians at a time and spread them out on the stage.

At first, we thought this was an unfortunate compromise we were making for COVID: I usually don’t want to record ‘classical’ music this way, but it turned out to be a great advantage. I had a lot of control in the mix. I think the result is something that retains the acoustics of the Hill Auditorium, but has the texture and power you might only expect from major film scores

Is there a particular project you’re most proud to have been associated with?

A couple come to mind. Early in my career, I worked with the Philip Glass team on the third movie in the Koyannisqatsi trilogy: Naqoyqatsi (2002). I was in the studio with Philip, Michael Riesman and Francis Kuipers regularly for almost a year, music editing, programming keyboards, and doing sound design. Michael Riesman’s complete mastery of everything that happened in the studio and on the scoring stage was intimidating, but I learned a great deal from him during that time.

I took those experiences and applied everything I’d learned to my work with John Luther Adams. John’s orchestral piece Become Ocean really put him on the map. That album won Grammy awards and John won the Pulitzer. I’m very proud of that album.

One great story from that time is that we mixed Ocean in New York City, on the same floor as a major hip-hop studio. The rappers and producers there came over to listen to Ocean, and it felt like the best thing ever to have a big mix of musical cultures in the same room.

What kind of advice would you offer someone on building an Atmos listening system or studio from scratch?

First of all, it’s worth it. While you’re on the ladder with a drill, you might think it’s not worth the effort. Fortunately, you only have to get on the ladder once. After that, the speakers are set up and you’ll be able to enjoy them for years.

Second, if you’re a consumer, Atmos is very adaptable. You don’t have to go with the full 12 speaker array on day one. You can do 5.1 with some height channels, or get a soundbar and then add the rears later. If you’re a professional, you really should go straight to 7.1.4 or higher, since there are things you need to hear when mixing in the format.