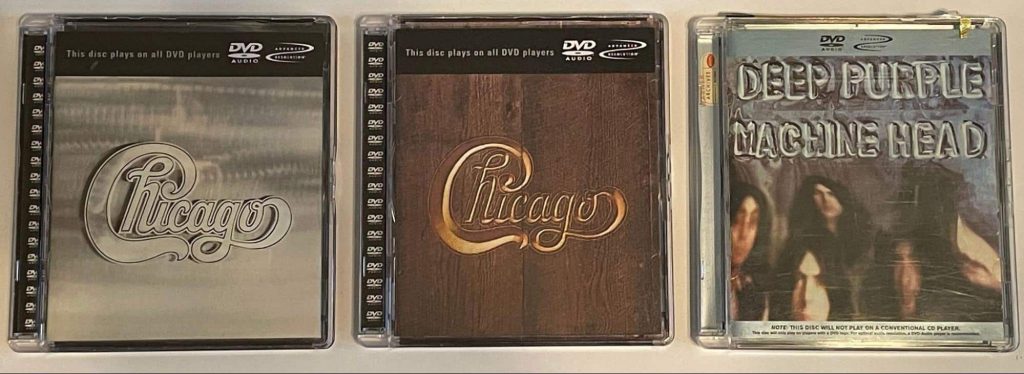

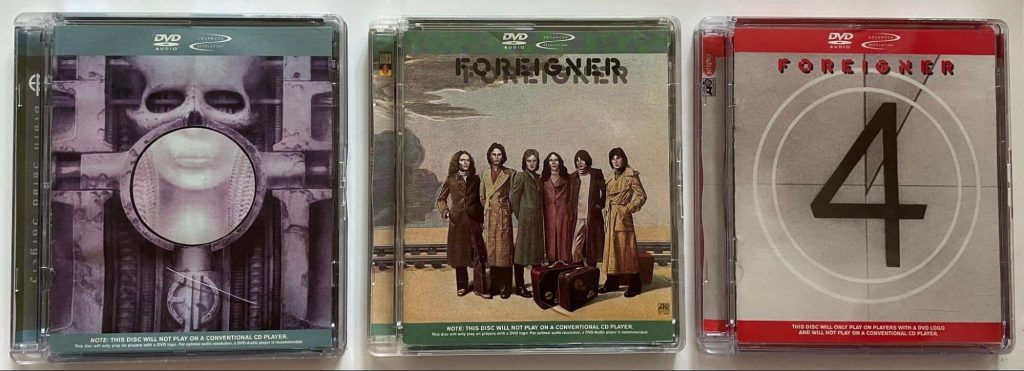

In 1992, John Kellogg produced some of the first 5.1 music mixes for the introduction of the Dolby Digital (AC-3) codec on Laserdisc. He has also produced 5.1 surround sound albums of several rock classics for the major labels, such as now out-of-print and sought-after 5.1 DVD-Audio releases of Emerson Lake & Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery (1973), Deep Purple’s Machine Head (1972), Chicago’s self-titled second album (1970), and Foreigner’s 4 (1981).

In the years prior to these projects, Kellogg started his path to success with a new-wave band called Combo Audio. Their first single, “Romanticide,” received national recognition from Billboard and resulted in their signing with EMI America to record an EP entitled The Original (1982).

We had a chance to chat with John about his early career, what kind of immersive projects he’s currently working on, and how he thinks recent strides in immersive audio will shape the music industry in the years to come.

How did you first get into engineering and immersive audio?

I first got interested in surround and immersive audio back in the mid-1980’s. I was transitioning out of my rock ‘n’ roll artist career into the production side and started working at Shure Brothers in Chicago. I got my first surround sound demo there from one of the chief audio engineers. It was an in-house project that later became the Shure HTS surround system.

They put me in this room with a really nice hi-end surround hi-fi system and a bunch of laserdiscs. Most of the discs were movies, but a couple were live music concerts. I was gobsmacked and completely hooked. I stayed there for hours and thought, This is amazing - this is how everything should sound. From then on, I was an advocate for immersive sound and it turned into a career.

I first crossed paths with Dolby Labs around ‘87-’88, as they were getting ready to license Dolby Pro Logic surround as a consumer format. I had left Shure Brothers and relocated to Los Angeles to work at a recording studio and music production company. Dolby recruited me and said, “You know about this surround sound thing, come work on it for us.”

Around ‘92, 5.1 came around. As far as I know, I produced the first ever 5.1 music tracks as demonstration of the format for the launch of Dolby Digital 5.1 as a consumer format at the 1993 CES show in Las Vegas with Pioneer Electronics. We auditioned 5.1 remixes of two Emerson, Lake & Palmer tracks from their Black Moon album and two Earth, Wind & Fire tracks from their Millennium album. These 5.1 music tracks were featured along with some clips from major films on LaserDisc and that kicked off the whole concept of 5.1 music. It turned a few heads.

I left Dolby for a while in the mid-90’s. DTS had launched by then and they were aggressively promoting DTS 5.1 music on CD’s, starting the 5.1 music concept. Around 1997, Dolby recruited me back to work on launching 5.1 music for DVD-Video with Dolby Digital and eventually to begin work on DVD-Audio. For the next several years, 5.1 music was my existence. I ran around the world working with studios, mix engineers, mastering engineers, and producers to get 5.1 surround albums made. Eventually, I produced and mixed a number of albums myself for Warner Music Group, Arista, and some indie labels. It was an exciting time.

Around 2005, I launched a start-up for downloadable 5.1 music not unlike what IAA is doing now. Until recently, it seemed like 5.1 surround music was over. That’s one reason I’m delighted to see IAA continuing and re-introducing the downloadable 5.1 music files concept.

In 2011, I left Dolby again to join SRS Labs to start developing an object-based audio format called MDA (Multi-Dimensional Audio), now known as DTS:X. We introduced it privately at CES around 2011 or 2012, again with demos of movies and music. This was the start of immersive. Dolby introduced Atmos for cinema shortly after. By 2013, SRS Labs was acquired by DTS and we continued our work developing and promoting immersive audio today. Eventually, I built my own immersive studio and mix room at my home which is where I do everything now. Now, with Atmos and spatial audio, immersive music appears to be roaring back and I couldn’t be happier about it.

Combo Audio was one of your earliest projects. Can you talk about the making of The Original?

It was recorded in 1983 at Pierce Arrow recorders in Chicago, where the band was based. We performed shows all over the Midwest, headlining clubs and opening for bigger acts like Talking Heads, Duran Duran and The Tubes. We got a lot of radio play and were darlings of college radio, which is how bands broke out back then. We released an indie single, “Romanticide,” which was a Billboard top pick and that started all the major labels after us.

We eventually signed to EMI, and they wanted to get an EP out fast because of the success of “Romanticide.” We recorded it in a couple of weeks, maybe three. We had Ian Taylor producing, who came over from the UK after doing Psychedelic Furs and working with The Cars. We flew to Boston and finished the record at The Cars’ Synchro Sound studios. We did all the 80’s band stuff: shot an MTV video, toured, all the usual stuff. We were a very tight, very loud three-piece rock band that had a lot of songs, grooves, stomp pedals, and eclectic ideas.

Over the years, I managed to acquire all the multi-tracks and masters of The Original. I was never that thrilled about how the record sounded originally, it was the 80s and had a bit too much polish for me. The past year has afforded me some time to revisit it and remix it to sound like the way I always wanted it to. It sounds pretty current even today.

In the early 2000s, you and Paul Klingberg had the opportunity to remix a number of high-profile albums by artists such as Foreigner, Chicago, Deep Purple, and ELP. What was it like working on these projects?

Oh, it was great. We were the ‘classic rock guys’ for a time and a lot of those classic rock albums came our way. I loved it. Getting to revisit those records I grew up with was fun and at times a bit overwhelming to get so close to that music and performances that were so much of the fabric of the era.

Were the artists usually involved in the remixing process?

In some cases yes, and in some no. We did Foreigner’s self-titled debut and 4 with Mick Jones involved. His stature as a producer was a little daunting to me at first, but he could not have been more supportive and great to work with. He would come in every few days and listen to what we had done, then make suggestions and give us notes.

Some of the tracks from the first album brought back a lot of memories, which I think were rather emotional for him. He hadn’t listened to those tracks for a long time.

He told us some great stories, like the origin of the lyric “Cold As Ice.” It did not come from a bad relationship, but from himself and Lou Gramm sitting in his apartment in NY during a bitter cold winter night plonking out the chords to that song and they just starting singing “it’s cold as ice.”

He also shared the demo tapes that got Foreigner signed, which we ended up including on the DVD-Audio release. Lou Gramm was involved near the end, as we did a commentary track with him and Mick. Lou was one of the nicest rock ‘n’ roll people I ever met. I was not a fan back in the day, but became one after working on those records. When you solo’d Lou’s voice, he was spot on in both pitch and rhythm. When I mentioned this, he laughed and said, “That’s because Mick would make me do it a million times until it was right. No computers back then, kids.”

While working on Deep Purple’s Machine Head, Paul and I got to mix “Smoke on the Water” which was an iconic classic rock anthem of our high school days. I used to watch buddies burning rubber, smoking their tires doing neutral drops in the high school parking lot while blasting “Smoke on the Water” on an 8-track in their cars. Decades later, Paul and I were working on it one evening and we just had this moment where we looked at each other and shouted, “Do you realize what we’re doing? We’re mixing freakin’ “Smoke on the Water”! How awesome is that?”

Tell us about remixing Chicago’s classic second album in stereo & 5.1. The consensus in most audiophile forums is that it’s easily the best-sounding version of the album.

Chicago II is certainly one of the albums I’m most proud of. It was nominated for an award or two. It’s such an amazing collection of songs and arrangements from these talented young guys who toured all the time and spent the day charting songs in their hotel rooms. They were all in their twenties. Can you imagine any young bands doing what those guys did on that album today? No clicks, no midi, no auto-tune: they just wrote it, charted it, and played it. The writing and performances on that record are astounding, especially considering the time and circumstances.

Paul and I struggled with the fact that there is a lot of midrange in that band. The horns, vocals, guitars, and keyboards all reside in the same frequency range, and there wasn’t a lot of high-end or low-end on the recorded tracks. There was a certain ‘anti-fidelity’ to it because in those days, everything was mixed for AM radio. The idea was for the song to punch through the radio, especially in your car. I was told that they originally mixed and checked everything for finals on a table-top radio sitting on the console. A lot of work had to be done, particularly on Paul’s part, to pull some fidelity out of the tracks and arrange all these midrange sources to get them out of the way of each other. We were really happy how it turned out.

One member of Chicago represented the band to listen to and approve the mixes. During mastering, he struggled when we played the first few tracks. He was so used to hearing the original from 35 years before. We put on a copy of the latest stereo remaster, which of course sounded tiny, then went back and played the 5.1 mix. He looked at us and said, “I get it, this is great.” By a few tracks in, he was loving it.

It is sometimes a challenge for artists of these classic albums, as they are used to hearing the music a certain way. When it’s opened up in 5.1, it can sound as if you’re hearing it for the first time.

Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery is one of my favorite 5.1 remixes. It’s one of the most extreme uses of immersive technology that I’ve experienced, with lots of swirling effects and aggressive deployment of the rear speakers.

Yes, we did go nuts on that one and rightly so. They were a band of spectacular extremes and that album was wonderfully over-the-top, so it felt appropriate for the material. There may not be an album more suited to showcase 5.1 than that one.

I had worked with ELP prior to remixing Brain Salad Surgery and got to know Greg Lake, who was a huge 5.1 fan. He was all for re-doing the record in 5.1 after hearing what we did with the tracks from Black Moon. ELP used to do arena shows in the 70’s in quad. Their live front-of-house mixer used to pan stuff all over the place, so they were no strangers to surround sound. Greg gave me some tapes of the “off the board” live quad mixes to listen to. We took a bit of inspiration from those live tapes panning the synth solos around. The sequencer synth spinning faster and faster in a circle at the end of “Karn Evil 9” was modeled directly after what they did at the end of their shows, when they played that track as a finale.

Ginastera’s “Toccata” was a masterpiece to begin with, and ELP’s rock approach to it was frankly revolutionary. I believe it was one of the first 24-track rock recordings. The rest of the album was 16-track. It featured Carl Palmer’s first electronic drum kit solo, and we were excited about what we could do with that in 5.1. We were remixing that album on multi-track tape, using a Studer machine. Once we got all the tracks set up, we discovered that all the different synth drum sounds were recorded directly to one mono track. It took some outside-the-box thinking to make that work in 5.1.

The first and second movements of “Karn Evil 9” were recorded as one continuous take, nearly 15 minutes long on tape. 15 minutes! The energy in that track was amazing, but it was exhausting to mix. We decided to mix it the way it was recorded, rather than cut it into sections. Just listening to it back was 15 minutes, but it was worth it in the end.

The other thing I remember was the track layout. Only four tracks for Carl’s drums: kick, snare, and a pair of overheads for everything else in that monster kit. Another few tracks for bass guitar, Greg’s vocal, Greg’s guitar, and a background vocal or harmony. The rest was all Keith: lots of hammond organ, synths, and one piano. There were harpsichord parts in “...Still You Turn Me On” that never were used.

Once the album was finished, I flew to London and booked some time in a 5.1-equipped studio (there weren’t many at the time) so Greg could listen to it. We started off playing the first track, “Jerusalem”, good and loud. By the second verse, he was singing along with it - so I knew he was happy and we were good.

There’s a lot of debate over the remixing of classic albums, as some fans feel there’s an element of “revisionist history.” Did you feel any obligation to closely replicate the instrument balances and effects from the original mixes? Or was the goal to create a completely unique take?

It’s a balance. You have to be true to the music and original intent. It was important to us to keep the original feel of any of the albums we did while at the same time making it seem bigger and better. We took that very seriously. At the same time, doing any remix, particularly in 5.1, intrinsically does create a unique take on the material. You want to maintain the original flavor, intent, and vibe of the music, yet put it into this bigger dimension and offer a new perspective on it. When we were working on Brain Salad Surgery, I called Greg and assured him that we were going to do everything to maintain the integrity and sound of the original album he had produced. “What?!” he said, “Why?! Make it better. If we could have done it in 5.1 back then, we would have. Don’t make it sound the same. Make it better, bigger, more spectacular!”

I don’t buy into the overtly purist B.S. saying you shouldn’t re-do these records. If the artist is down with re-doing it, then by all means let’s re-do it and let’s have fun with it. Most artists I have worked with or know would love to have another crack at remixing their work, particularly in 5.1. If not, then leave it alone.

I imagine there’s a lot of detective work behind-the-scenes involved in trying to piece these albums back together from session tapes, locate all the correct takes, etc. Have you ever faced such challenges?

I likened it to an archeology expedition. You dive into the track sheets and try to figure out what they were doing back when the technology, gear, and number of available tracks to record on was so much more limited than today. A lot of those albums were originally recorded on 16-track analog tape. “Lucky Man” by ELP, which we mixed as a bonus track for the Brain Salad Surgery DVD-Audio release, was only 8-track. There was a lot of track stacking: “Oh, here’s an open section in the backing vocals track, put the guitar solo there.” We had to split a lot of stuff out.

On Deep Purple’s Machine Head, we found entire drum breaks that were recorded on separate tracks then mixed and spliced into the 2-track master reel. It was fascinating and a little mind-bending at times to make it work in 5.1. We also found an entire song, “When A Blind Man Cries,” that had never been mixed or released. So we mixed it, and it was included on the DVD-Audio release.

When I was preparing to remix Foreigner 4 in 5.1, the multi-tracks for two songs were missing. I was back-and-forth on the phone with the label vault people, who were great, but they simply could not find the tapes. We started to think we would have to scrap the project when the vault finally called me and said they had found them. It turned out that the tapes were in the wrong boxes labeled incorrectly as another project. They found them when they noticed that all the tapes for that album were in green boxes. So they started looking in all the green boxes and eventually found the multi-tracks for those two songs and their track sheets.

Another aspect of doing those older albums was the tapes all had to be baked. As analog tape ages, depending on the brand or oxide configuration, it starts to disintegrate. The oxide starts to come off, especially when you try to play them. So you have to literally bake the tapes at a specific temperature for a specific period of time, then you can safely play them for a limited time. Often when you bake tapes and copy them over to digital, you get one shot at it.

We did a lot of research and there were a lot of expensive services and ovens, but finally we found the best method to bake them. We found a guy who had done a ton of testing and research and he published his findings. The best method was – wait for it – 23 hours in an American Harvester Food dehydrator at around 125 degrees, then let them cool down for another 24 hours or so and you’re good to go. It worked great. It also turned out that the food dehydrator, which was circular, was exactly the perfect size for a two-inch reel of tape. If you cut some of the internal stacking trays, you could put two reels per dehydrator. At the time, the food dehydrators were silly cheap, like 75 dollars or something like that. We copied the tapes over to new 24-track reels (we were still working analog then) and worked off of the new multi-tracks.

There are many different mixing styles used by engineers. Some are more conservative and use the rears primarily for reverberation, while others are more experimental and place isolated instruments behind the listener. Your 5.1 mixes seem to lie somewhere between those extremes. Can you talk about your decision-making process when using the extra channels?

My decision-making process was and is simple. It is all driven by the music. The 5.1 mix should be entirely determined by the music.

I used to sit on some surround music producing panels back in the day and listen to other producers pick apart mixing in surround and come up with all kinds of analysis of the approaches: the “audience mix,” the “stage mix,” the perspective you should create. They’d come to me and I’d just sit there and say, “I dunno, we just work on it and mix it until it sounds cool.” If something screams to be panned around or put in the surrounds, put it there. Just don't do it to be gimmicky and fling stuff around for the sake of it. I’ve been guilty of that myself in the early days. Do the music justice.

I dislike what I call lazy 5.1 mixes, where someone throws some reverb or a couple instruments back into the surrounds with essentially a stereo mix in front. That’s disrespectful to the music and the art of surround. If you’re going to mix something in 5.1 or immersive, do it well. Think it through. Make the mix feel cohesive. Give the listener a chill or a thrill, something respectful to the music and an experience they’ll want to hear over and over.

To that end, I need to make a point here: The music itself drives the experience. 5.1 or immersive are tools: they should not distract from the music. A bad immersive mix can ruin a piece of music and taint the whole potential of the experience. I’d rather listen to a great stereo mix than a bad surround mix, and there’s some very lame surround mixes out there.

Any current projects you’re working on?

There’s another album or two of Combo Audio and solo rock stuff that was never released, so I’m working on getting that all finished and out. The good thing about the current distribution model of music is that complete DIY is easily possible. If you have the wherewithal, you can produce and distribute your own stuff without a label. There’s a lot of downside to the current streaming model, but there is upside as well. What’s great is now 5.1 surround and immersive music can be done DIY as well.

I’m also excited to work on some ambient music that I’ve been focused on. Some from me and some from other artists. Ambient music is a long-time passion for me. It’s tailor made for 5.1 or immersive. I’ve mixed a fair amount of it in the past for friends and artists on Spotted Peccary music. David Helpling, Jon Jenkins, Deborah Martin, Howard Givens. I’m really looking forward to working on that.

Have you had the opportunity to mix in an object-based format with height speakers, like Dolby Atmos or Auro-3D?

Yes, indeed I have. I did a lot of early object based immersive mixes as proof of concept during the development of MDA object-based audio, now known as DTS:X. I’m quite familiar with 7.1.4, Atmos, DTS:X. The new Combo Audio mixes are all available in Atmos as well as 5.1 and stereo. My studio at home has been equipped with 7.1.4 for years. I have not had any experience working in Auro-3D, but have heard the film versions of it. Kudos to Apple and Dolby for finally making immersive and spatial audio mainstream. I’ve been waiting a long time for that to happen, so I’m really excited that surround and immersive audio, something I’ve believed in and spent much of my adult life on, can now become a de-facto way of enjoying music or any audio presentation.

What surround sound system do you use at home?

I have my studio at home, so I’m fortunate. That’s where I do my listening, at least on speakers. I’m also an avid headphone listener: if I’m not in the studio, I’m on headphones. To be honest, that’s where I check all my mixes before I print them for release. Those headphone checks govern final mix decisions for me. Why? Because that’s how they’re going to be heard by most people.

In many ways, it’s as important to me how stuff sounds on headphones and earbuds as it is on speakers or in a car, because that’s what everyone is listening to. This applies now to 5.1 and immersive. Again, Apple, Dolby, DTS, and others are all raising the bar and making it possible to have a great immersive audio experience on any set of headphones. It’s a cool time for audio again.