Over the past 40 years, Ronald Prent has established himself as one of the most accomplished and innovative mixing engineers in the world, specializing in surround sound and immersive audio. His long list of clients includes Celine Dion, Simple Minds, Freddie Mercury, Dire Straits, The Police, Simple Minds, David Knopfler, Rammstein, The Scorpions, Mink DeVille, Elton John, Cliff Richard, Tina Turner, Queensryche, Def Leppard, Udo Lindenberg, Herbert Grönemeyer, Peter Maffay and Manowar.

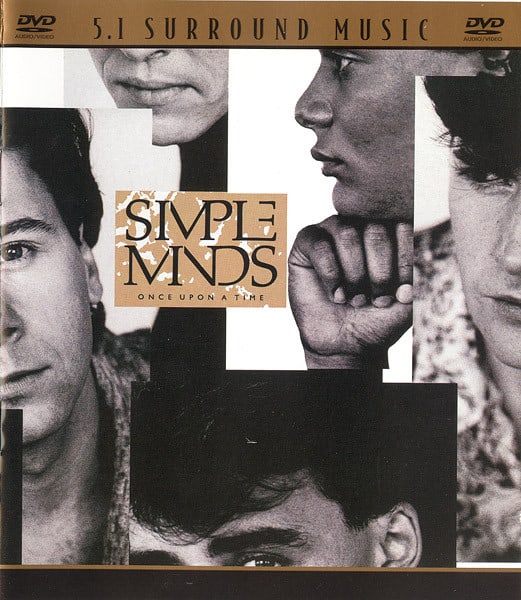

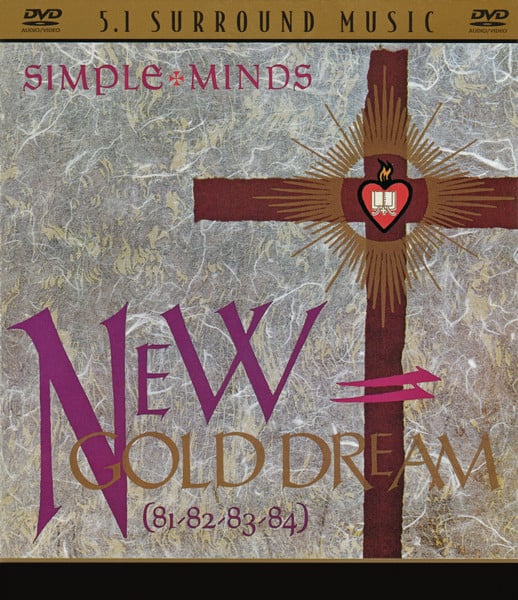

Over the past two decades, Prent has created dozens of excellent 5.1 mixes for Super Audio CD, DVD-Audio, and Blu-Ray Audio releases. Key examples include Simple Minds’ Once Upon A Time, Hooverphonic’s No More Sweet Music, Mando Diao’s Aelita, Lori Lieberman’s Bricks Against The Glass, and Kane’s So Glad You Made It, which earned him a Horizon Surround Music Award in 2003. In 2018, he received a Grammy nomination in the category of “Best Immersive Audio Album” as producer and mix engineer for Symbol, his collaboration with Prash Mistry’s Engine-Earz Experiment.

We had a chance to chat with Ronald about his early career, how he became involved with immersive music, and how he thinks the new object-based immersive formats will shape the music industry in the years to come.

Tell us about your early career. What made you want to pursue a career in audio production/engineering?

I was already interested in audio at a very young age. My father had a tape recorder and he worked for a hospital Broadcasting System in the Netherlands, which was charity work.

I was always helping run cables and eventually ended up at a radio station in London, working as an editor for the news shows in the morning. From that point on, I became even more interested in the technical work behind the broadcasts.

The record company Phonogram, which is owned by Philips and later became part of Universal, had a studio and office in the town where I was living. They had just finished building a brand-new recording facility in the woods there called Wisseloord Studios, which had a job opening for an assistant trainee.

After a short selection period, I got the job. Initially, all they had me do was make coffee and clean up the mess from the sessions that ended at five in the morning. Then, I’d have to set up the next session at eight in the morning.

After doing that for two years, they offered me a steady position as an assistant engineer.

One of my first big jobs as an assistant engineer was when The Police came to record Zenyatta Mondatta (1980). That was a two month session, and it was of course the best place to be as an assistant engineer because you're working with a top band and top producer. What better way to learn what to do and what not to do?

I stayed at Wisseloord until around 1987, when I became a freelancer and started traveling to Europe. During that time, I worked in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, England, and a couple times in the United States.

How did you become interested in Immersive Audio?

During the late ‘90s, when Sony and Philips started developing the Super Audio CD (SACD) format, I was asked to join that project by colleagues I’d previously worked with at the Phillips Research Center and the classical recording branch of Polygram. They wanted to know if I was interested in figuring out how to mix music in 5.1 surround.

Phillips brought us to one of their facilities to demonstrate what they’d been working on for SACD. They played me a classical recording in 5.1 that I’d actually recorded in a South London chapel.

They didn't tell us ahead of time that during the recording, it had actually started to rain. I was sitting there and actually thought it was starting to rain, because the perception of dimension in height and depth was just amazing. That was the moment when I was converted.

From that point on, I knew I wanted to mix music in a multi-channel format. The first big one that I did was for a German band called Guano Apes, which is still a benchmark for 5.1 mixing.

During that period, I moved from Wisseloord to Galaxy Studios in Belgium, which, at the time, was the only studio in Europe that had a real 5.1 control room.

Nearly a decade later, the opportunity came for my wife, Grammy Award-winning mastering engineer Darcy Proper, and I to move to the United States. That’s where we currently are based, in upstate New York, where one of my oldest clients, Joey DeMaio from the heavy metal band Manowar, had a beautiful church. He's an absolute immersive audio freak, so we turned the church into a great new immersive studio.

This was around the same time that the new Dolby Atmos, Sony 360 Reality Audio, and Auro-3D immersive technologies had emerged, so we've created this place where you can mix in all three formats using both analog and digital components. That's, in short, my path from 1980 until today.

Can you elaborate on the differences between Dolby Atmos, Sony 360 Reality Audio, and Auro-3D?

Yeah, they're apples and oranges. Auro-3D goes up to 13.1 and actually now also allows for objects. The speaker base format is very easily adapted to Sony 360 or even Dolby Atmos, so it’s the best starting point.

Sony 360 is mainly a headphone format, although I understand it’s compatible with some soundbars and wireless speakers. They're completely different animals, and that makes my life very, very complicated.

If the client hasn't decided what format to use, then I will mix the project in Auro-3D. On the other hand, if I know it will be streamed on Apple Music, then I will start mixing it in Dolby Atmos.

If you mix directly in the format of choice, you get the best result. Dolby Atmos, especially on speakers, sounds amazing. I recently did a live concert in Atmos that’s really immersive, but if you take that and adapt it to Sony 360, it doesn't work as well.

If you have a client that's not sure which format to use or wants multiple versions, then you have to compromise. The best way to do that without spending six days on a song in three different formats is to create a discrete 13.1 mix. I'll mix it on speakers until I'm really happy with the result, then I put on my headphones for Sony 360 and tweak it.

Once I’ve printed that, I'll step back and try the discrete 13.1 mix through the Dolby Atmos speaker configuration. Sometimes it’s mappable to Atmos, but about 80% of the time I’ll end up re-assigning some instruments to object-based positions. So, the 13.1 offers a good starting point and offers flexibility going into the other formats

What if the client wants a standard 5.1 mix? Do you simply fold-down from the 13.1?

If there's time, I prefer to do a separate mix in 5.1 on the console. It just sounds better and more coherent, because folding-down or down-mixing can often have unforeseen consequences. Sometimes it works well, but other times there can be issues where instruments become too loud or disappear entirely.

Since I work both analog and in-the-box, my console allows me to do separate 5.1 or stereo mixes alongside my immersive format. I always make a discrete stereo mix as well, because the client often requires that the stereo mix be identical in length to the immersive mix.

In the early-2000s, you had the opportunity to remix Simple Minds’ classic albums New Gold Dream (1982) and Once Upon A Time (1985) in 5.1 surround for DVD-Audio release. What was that experience like?

The thing with classic albums is that you have to be very careful not to stray too far from the way they originally sounded. Bob Clearmountain originally worked on those albums, and was very generous in sharing how he treated the vocals and what kind of reverbs or delays were used.

As an experiment, we actually tried auto-tuning the vocals on one of the songs since it wasn’t quite in pitch. I played the new mix for some people and immediately saw on their faces that something's not right. The vibe is not the same, even though I’ve copied nearly every detail of the original. So I switched back to the original vocal treatment with Clearmountain’s reverbs, delays, and pitch-shifters.

I didn’t realize how big a difference that one change would make in how the music was perceived. You have to stay very true to the original production and adapt it to 5.1 without crossing certain boundaries. Just because the drummer skipped a beat somewhere or the bass player missed a note doesn’t necessarily mean you can go back and fix it.

There are so many different immersive mixing styles used by engineers. Some are more ‘conservative’ and use the extra speakers primarily for back-of-the-hall ambience, while others - such as yourself - are more experimental and place isolated instruments behind or above the listener. Can you take us through your decision-making process when using the extra channels?

There’s definitely a learning curve. In the beginning, you tend to experiment with movement and that doesn't always work. If I decide to fly something around, I'll have a good reason for it.

Basically, you want to create a new experience and environment where the listener can sit inside the music. They don’t necessarily have to sit in the best spot, they can also walk around-the-room and hear it from a different perspective.

Once you’ve created a virtual space within the five speakers, it immediately gives you the freedom to use every position to its full extent. I can isolate a vocal in the center speaker or I can put a heavy metal guitar in the left rear to blow your pants off.

In short, I’ll take the different elements that are available to me in the mix and put them in positions where they actually extend the arrangement and add excitement to the song. Once I’ve done that, the artists tend to say “Whoa, now that's how I always heard it in my head.”

That is a great compliment to receive, because then you know that you've hit the right button with the artist. We used to have only had two channels to work with, this narrow tunnel we had to squish everything into. Now, you have anywhere from five to thirteen full-range speakers! The possibilities are really endless.

It’s also worth pointing out that anything out of your 120-degree vision is considered hostile by the brain, so having loud elements unexpectedly emerge from the rears can frighten people or make them smile. That makes for a more exciting experience than simply having the vocals come out of all the speakers at once, which just creates a big mono blob.

It’s interesting that you mention isolating a vocal in the center speaker, as that’s a hotly-debated mixing technique among immersive fans. I know that some engineers tend to avoid doing that since many listeners’ center speakers tend to be smaller and not matched with their front pair.

It can work with smaller speakers as well, because the trick is to reinforce the vocal signal in the left, right, front, and rear. In order to avoid introducing comb filtering, these vocal reflections in the other speakers needs to have a very short delay time.

You put those additional delayed signals at -20 dB under the relative level of the centered vocal and all of a sudden, it doesn't feel isolated anymore. You take them away and the vocal feels extremely isolated. George Massenburg and I spent a lot of time figuring that out. It's all psychoacoustics, how your brain perceives what you hear.

If that doesn’t work, sometimes I'll put the vocal in the phantom center instead of the actual center speaker. It's all a matter of preference, but I love doing the center-isolated vocal if I can make it work.

I've even heard examples where the harmony vocal is placed in the phantom center and the lead vocal is in the center speaker. It’s an interesting effect, since both voices are isolated in different physical speakers yet they still occupy the same position in the mix.

I actually did that with a duet. The female singer in the center speaker and the man in the phantom center worked great. I also did a father and son duet where the voices alternate between front and rear. People love that because all of a sudden, this guy unexpectedly appears from the rear and sings.

One of my favorite 5.1 mixes you worked on is Lori Lieberman’s Bricks Against The Glass (2014). During the song “Rise,” there are multiple vocalists positioned all around the listening space. It’s a demonstration-quality moment.

Yeah, for sure. Again, that's a great example of how mixing in immersive can enhance the arrangement of a song. That extra level of excitement and immersion is exactly what I’m looking for.

Do you get special requests from your clientele for immersive mixes? Or is working with you typically their first exposure to 5.1 or immersive music?

It was always the latter of the two. I’d mix for stereo first, then show them how their music could sound in 5.1 or immersive. Of course, COVID has since made it impossible for me to do those live demonstrations. Lately, it’s been the opposite: “Can you do an immersive mix?” or “Can you then also deliver the stereo for me?”

Any current and/or future projects involving immersive audio you can tell us about?

I'm currently working on three different projects, all slated for October or November release. I've just worked on a high-profile single in immersive, but I can’t reveal what it is because the client has big marketing plans.