Alan Williams was a founding member of New England-based Knots and Crosses, who signed an ill-fated deal with Island Records in 1994 after self-releasing two best-selling CDs. He went on to a career in studio engineering and production working with Patty Larkin, Jennifer Kimball, Lucy Kaplansky, The Nudes, and Stephanie Winters among others. He served as musical director for Dar Williams and Cry Cry Cry before turning his attention to academia, earning a PhD in ethnomusicology from Brown University and becoming a Professor of Music at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

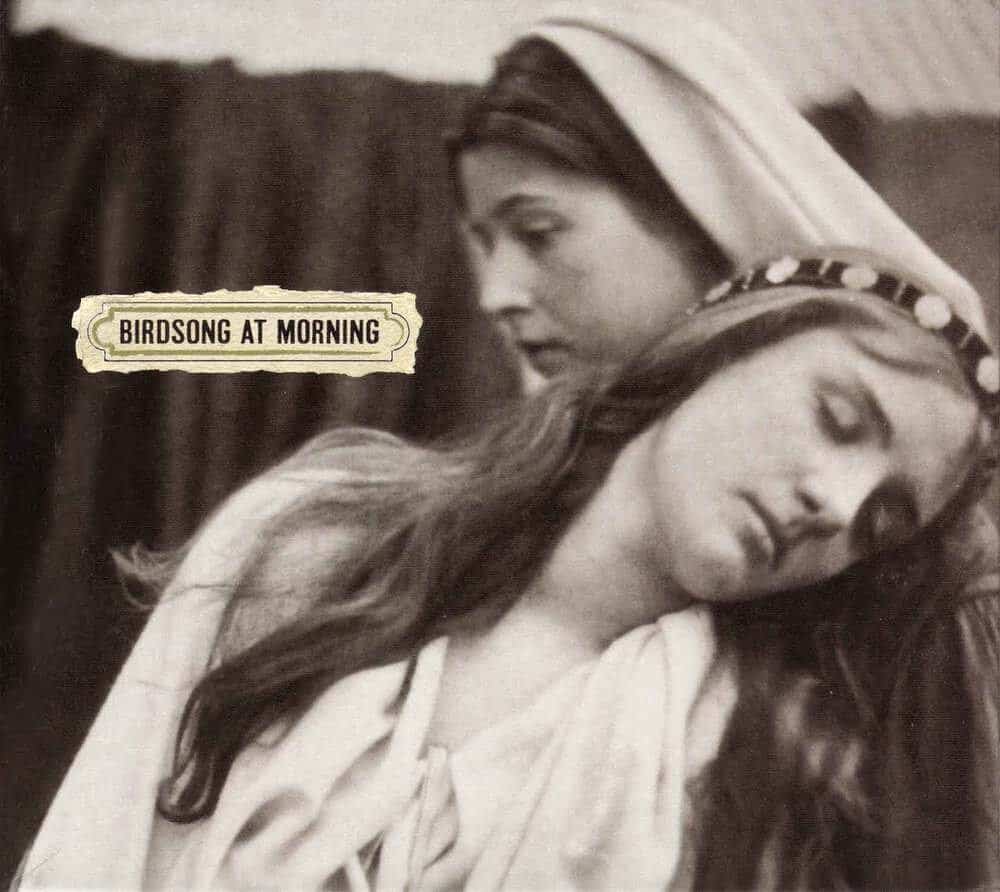

In 2007, he reclaimed his identity as a performing musician, forming Birdsong At Morning with Darleen Wilson and Greg Porter. Two of the band’s albums, A Slight Departure (2015) and Signs and Wonders (2018), were released as CD/Blu-Ray packages with all songs in both stereo and 5.1.

Alan continues to perform both solo and with Birdsong At Morning, and is presently working on a new album slated for release in 2022. We spoke with him about his early career, his unique approach to songwriting and arranging, and how he became such a strong proponent of immersive music.

Tell us about your early career. What made you want to become a musician?

There’s an old story my mother tells. When I was three years old, my parents took me to see The Sound of Music on the big screen. The next day, while my mother was in the kitchen, she noticed that the random plunking on the piano in the next room was starting to coalesce into “Do-Re-Mi.” She walked around the corner to find me standing at the base of the piano, reaching over my head without seeing the keys and roughly working out the melody. A teacher was called. Lessons began.

I played piano fairly seriously through high school and got into the New England Conservatory of Music to major in Third Stream Studies, now known as Contemporary Improvisation. As part of their approach, I was given the choice of classical or jazz piano, and I opted for jazz having fumbled my way through some Real Book tunes and under the spell of Bill Evans and Keith Jarrett.

When I went for my first lesson, I was stunned at the level of musicianship I heard leaking from under the door of the teacher during a lesson. I had an instant crisis of faith, questioning my very existence as a human being (“I can’t play that, which means I’m not a piano player. Which means I’m not a musician. Which means I’m… worthless”). Fortunately, the powers that be were sympathetic enough to ask what I might want to do instead. I mumbled something about songs and singing, and to my astonishment, was reclassified as a dual composition/voice major.

In that environment, virtuosity was everywhere. That being said, sometimes that virtuosity lacked a coherent idea. That’s the niche I began to inhabit. In the groups I played with, I frequently became the de facto arranger, and when we began entering recording studios, I found my true calling as a producer. It just took me a few decades to realize all of this. It should also be noted that I have had the great fortune to make music with Greg Porter (a founding member of Birdsong At Morning, and a friend for over 40 years) and Ben Wittman (a staggeringly talented drummer and producer) for the totality of my professional life from conservatory days to the present.

Was it difficult transitioning from a music career into academia?

After NEC, I was a member of Knots and Crosses, a folk-rock band that had phenomenal success with our self-released CDs in the early 90s, only to implode when we signed a deal with Island Records. Fairly burned by my flirtation with the music business, I fell into work as a freelance engineer and producer (when I wasn’t managing a video store). I lucked into an opportunity to serve as a last-minute replacement for a lecturer to teach a course entitled Music, Technology and Society. No teaching experience, only a Bachelor degree, and working from a one-page outline, I taught myself how to teach. Soon, I began hoping my studio dates would fall through so I could do more teaching.

Clueless as to how academia works, it took a few years before my mentor enlightened me that I had no future without an advanced degree. So, to be sure I didn’t ever have to work in a video store again, I earned a PhD in ethnomusicology from Brown University. The great thing about that time was playing in all the various world music ensembles where I reclaimed the joy of music making without a professional agenda. And as an avoidance mechanism when I should have been writing my dissertation, I took up guitar. Next thing I know, I have a doctorate and a tenure-track job. Now, I’m a full professor and part of the research I’m paid to conduct includes writing, recording, and performing my songs. It’s like a record deal without the A&R department pressuring me for a single.

How did you first get into engineering and immersive audio?

I’ve been engineering for many decades now, usually in low-budget studios where one has to maximize the impact of sound with a modicum of tools. I’m also a film buff and put together a decent audio system in 5.1, initially for watching movies. After picking up a few DVD-Audio titles, I became fascinated with the possibilities of immersive audio. I wondered why some albums became transcendent, while others fell apart in surround.

As a listener and music fan, I wanted to see if I could create an expanded environment for my own music. Fortunately, my first DAW was Cubase, and when Steinberg introduced Nuendo, I ported over to that software. Nuendo was designed for film post-production and initially had the jump on Pro-Tools with working in surround. So I didn’t have to invest in anything new (other than additional speakers) to dip my toe in the water. After completing the first Birdsong At Morning project, I decided I’d try a surround mix of the next album and here I am today – fully committed to immersive audio for my musical expression.

There are so many different immersive mixing styles used by engineers. Some are more conservative and use the rears primarily for reverberation and room ambience, while others are more experimental and place isolated instruments behind the listener. Your 5.1 mixes seem to lie somewhere between those extremes. Can you talk about your decision-making process when using the extra channels?

Part of my academic life has involved thinking and writing about the process of creating music in recording studios. There’s a research cohort and journal called The Art of Record Production, and at one of those conferences I had a chance to talk with Steve D’Agostino who had done some surround work with David Sylvian, a musical hero. He cautioned me to finish the stereo mixes completely before embarking on the surround – solving problems in stereo will make the surround mix a dream whereas the converse is definitely not true.

I began to study what Steven Wilson was doing with the early prog-rock reissues of King Crimson and Yes. In some cases, working from only 4-track or 8-track tapes, his surround mixes felt expansive without falling apart. I noticed the drum kit sat somewhat in the middle of the room, present in both front and rear. When he had more isolation between signals, he could create a sense of sitting at the drum kit. The first rack tom was slightly in front and to the left for example, but only slightly so that the drums never felt disembodied. That has become my approach as a starter.

Ambient signals certainly have greater depth spread from front to rear, and musical elements that aren’t fully integrated into the core can be placed in their own space, perhaps discreetly only in one channel. The idea is to feel you are surrounded by the sound of a band, yet able to direct your focus to the vocal, which is primarily, though not exclusively in the front L/R. Some folks cautioned me about using the center speaker, and I don’t put a lot of crucial information there.

I try not to put anything essential solely into the rears, since I’m aware that non-audio oriented folks often have mismatched/bizarrely-placed surround speakers in their homes. This might make for a boring experience under ideal listening environments, but I often recall a ‘lightbulb’ moment as a kid.

Growing up, there was a bulky console stereo in our living room. When no one was home, I would immediately throw on my Beatles albums. I loved the energy of their music, and the number of instrumentals they put on their albums seemed particularly creative. As it turns out, one of the speakers in the console didn’t work! My first few years of Beatles awareness were based on hearing only one channel of their stereo LPs. Everyone knows the often-bizarre wide panning to be found in those mixes (vocals in one speaker, band in the other), so imagine my surprise when I heard them playing in other people’s homes. Who knew there were vocals on most of their songs?!

I wouldn’t want anyone who bought my records to miss the vocals, unless they’ve purposefully chosen to listen to the instrumental mixes (always fascinating).

Tell us about Birdsong At Morning’s cover of Supertramp’s mega-hit “The Logical Song.” It's a pretty radical reimagining, yet the new arrangement and slower tempo actually seem to highlight the lyrics and underlying message of the song more than the original. Was it daunting to cover such an iconic hit song? Were you intentionally trying to make it as different from the original as possible?

I’ve been a big believer in the power of a new interpretation of an older work. Every Birdsong disc has a cover version of songs ranging originally by artists such as Blondie, King Crimson, Fleetwood Mac, The Rolling Stones, and Bobby “Blue” Bland. While I was writing songs for Signs and Wonders, I was feeling pummeled by the political and social unrest around me and thought about a cover song that might speak to the moment. Most of the songs we’ve covered were favorites of mine during my formative teen years, and this was also the case for “The Logical Song.” Once I stripped away their trademarked electric piano and slowed down the tempo, the meaning of the lyric became a little weightier, a little more specific. Rather than vaguely railing against the ominous presence of the digital watch, I heard a resonance with the lyric “they’ll be calling you a radical, a liberal, fanatical, criminal” that felt very of the moment.

The next challenge was to re-think the music so that it had a different kind of power. That’s why we built up to full on drums and orchestra during the outro riff that had previously served as the underpinning for a saxophone solo. I’m really pleased with the result, though I know some Supertramp fans were not as enthralled. I myself have become less of a fan due to frustrating issues with their publisher’s approach to streaming and synchronization licenses. For Signs and Wonders, we made a video for every song, including “The Logical Song.” I dutifully paid both a mechanical license for the audio and negotiated a sync license for the video. But the sync license does not include the right to stream in North America. Why? I don’t know. You can watch it in Europe and Asia, but not in the US. It makes me want to write an additional verse to the song.

Evidence Unearthed was a project 25 years in the making. What prompted you to revive those songs from so long ago?

One aspect of academic life is the continual updating of the resume/CV. I’ll include all the songs I’ve written, records I’ve made, performances given, as well as articles and book chapters. One day, I happened to notice a batch of songs listed that were not available to the public. I had completed the album in one form in 1995, but had a crisis of faith in it and ended up giving out a few copies to friends and storing the rest away on a shelf for decades.

I finally got up the courage to listen to the original version and realized the songs weren’t so bad, and that the band performances were quite strong. Really, it was mostly the vocals that revealed an insecurity/immaturity that brought down the impact of the music. So, I decided to re-sing the album, and remix for the new millennium, including of course a 5.1 mix. To my pleasant surprise, the original tracks were very well-recorded and held up after all these years. I ended up keeping many of the harmony vocals from the original, so at several points there are moments where 56-year-old me is singing with 31-year-old me. I’d like to think I’ve aged like a fine wine, though it might be closer to a fine whine.

Are there any plans to go back and remix Birdsong’s debut album, Annals of my Glass House, in 5.1?

Before I embarked on the Evidence Unearthed project, I was contemplating a remix of “Annals,” especially with an ear to 5.1. But the older version of Nuendo project files wouldn’t properly open, and I gave up in frustration. I’m sure a little (probably more than a little) online sleuthing could solve the problem, so there’s a very real possibility of an updated version in the future.

Any current projects you’re working on? New solo or Birdsong material?

Yes, I’m fairly far along on a new record composed during pandemic isolation and recorded in part via internet file exchange. Many of the songs have an energy informed by the Evidence Unearthed album, and I’m thinking it will probably come out under my name rather than Birdsong At Morning. Already thinking about approaches to mixing for 5.1, or possibly Dolby Atmos. Keep your eyes and ears open for it sometime next spring.

You can find selected works from Alan Williams in the IAA Shop!